PreCheck Won’t Save You From REAL ID, But Congress Might (2)

- PreCheck, CLEAR unacceptable ID now, but lawmakers mull change

- Foes of switch say it would raise privacy, fairness questions

(Updates with Thompson quote in eighth paragraph and polling data in 18th paragraph.)

As the Republican ranking member of the House Homeland Security Committee, Rep. Mike Rogers has traveled virtually every week between Washington and his home district in Alabama since 2002. To make it simpler, he had his identity, fingerprints and background screened by PreCheck, the Transportation Security Administration’s paid expedited screening service.

PreCheck allows him to more quickly pass through airport security checkpoints. But on Oct. 1, 2020, Rogers and others like him who lack driver’s licenses certified by the government as secure might not be allowed to get on planes, despite shelling out $85 for a five-year membership in the extra screening program.

“This is going to get uglier as it gets closer,” Rogers said in an interview.

As airports brace for their busiest holiday season ever, lawmakers from both parties say they’re increasingly worried that this time next year will prove to be a travel nightmare for U.S. passengers at security checkpoints—even those who have paid for services like PreCheck and CLEAR, who may think a membership makes getting an updated ID unnecessary.

Under a law passed in 2005, states have to upgrade their licenses to make it harder to get fake ones. To meet REAL ID Act muster, states must require applicants to provide extra documentation at their motor vehicle license offices. But foot-dragging by the states, ignorance of the new requirements by travelers, and the long lead time needed for people to cycle through to get new, upgraded IDs as old ones expire mean many travelers will lack acceptable identification by the 2020 deadline.

Paying to Cut Line?

One proposal being worked on by Rogers’ and Homeland Security Chairman Rep. Bennie Thompson’s (D-Miss.) committee would allow for PreCheck, and possibly CLEAR, another expedited screening program, to be used as alternatives for the new licenses.They’re also exploring pushing back the deadline.

“Everything’s under consideration,” said Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), chairman of the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee.

“The inconvenience for the traveling public is going to be astronomical,” Thompson said.

But some aviation industry groups worry Congress won’t move fast enough. And some civil rights and privacy groups, as well as some academics, say giving CLEAR—a private company—a government mandate without adequate oversight of how it handles citizens’ data raises privacy and security concerns. They also say the move would signal that wealthier Americans who can afford the services can buy their way out of what they consider the more onerous REAL ID process.

“CLEAR is a private company—basically you’re paying them to cut the line at TSA,” Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union. “If frequent travelers don’t comply with REAL ID like everyone else, they shouldn’t be able to pay out of it.”

For his part, Rogers said he’s worried some of his poorer, less educated constituents will struggle to collect all the documents needed and to potentially take time off of work to get a REAL ID-compliant license. He said his wife, Beth, a state judge, struggled for several weeks to get her new license, and at one point had to call him while he was on Capitol Hill while she was looking for the right documents.

Screening Speed

PreCheck and CLEAR are both services launched after the September 11 Commission’s report suggested an upgrade to state-licensing standards. Members of TSA’s PreCheck program usually apply online for a background check and are fingerprinted at airports or kiosks around the country to prove their identity.One perk of membership: They are allowed to pass through airport security in specialized lanes without having to take off their belts and shoes or remove laptops from their bags.

CLEAR is a private company that participates in TSA’s registered traveler program, but, unlike PreCheck, it is not directly overseen by the agency. Members pay $179 a year and can register at kiosks at about 35 airports, where they answer questions to prove their identity and employees collect scans of their fingerprints, iris, and face.In return, each time they fly, they are escorted to the front of the security line as the service replaces the need for a TSA officer to validate their license and boarding pass.

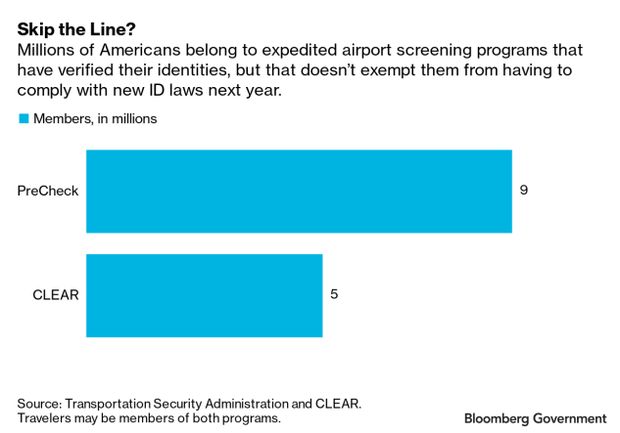

PreCheck has 9 million travelers enrolled, accounting for about 20% of TSA screenings daily, according to the agency. CLEAR expects to have 5 million enrolled members by the end of this year,or about 5% of airport traffic. It’s unknown how many people belong to both services.

The services are different than Global Entry and other paid programs for international travelers run by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which issue its own identification cards that can be used as Real ID alternatives.

Fourteen-Year Program

It’s unclear how many Pre-Check and CLEAR members lack a REAL ID, or an alternative document—like passports or military IDs—that the TSA will accept come October of 2020. But only 27% of all Americans have been issued a REAL ID, according to October data from the Department of Homeland Security. That translates into about 99 million Americans without a REAL ID or an acceptable alternative, according to the U.S. Travel Association.

Two states—Oregon and Oklahoma—will not even begin issuing their own compliant licenses until weeks before next October’s deadline, and New Jersey’s licensing process is still under review by DHS. Moreover, some Americans may be confused by states that continue to issue both compliant and non-compliant licenses, or live in states that don’t require frequent license renewals.

More than half of Americans are not aware of the October 1 deadline, according to data from the U.S. Travel Association, which estimates more than 78,000 travelers will be turned away and unable to fly on that day alone next year.

“The implementation of REAL ID is a 14 year-old program,” Tori Barnes, an executive vice president at U.S. Travel Association, said.

“That’s why folks who are in CLEAR or TSA PreCheck, which already have a higher level of security than what is required to get a REAL ID compliant license, should be viewed as being REAL ID compliant,” she said.

Government Supervision Needed?

Barnes’ group wants Congress to ease compliance, including allowing PreCheck and CLEAR as alternatives, as well as letting states accept mobile or online applications for the new licenses. Barnes says CLEAR has passed the government’s highest cybersecurity rating, and TSA administrator David Pekoske has previously said the service met its security protocols.

But some lawmakers and oversight groups and academics are particularly worried about allowing a private company like CLEAR to carry out a government mandate without oversight to ensure security and privacy, especially when the service collects sensitive biometric information.

“The government would have to really step in, in my book, and really oversee it,” Glen Winn, an aviation security specialist who teaches at the University of Southern California, said in an interview.

Others say it’s unfair to let Americans skip out of the REAL ID screening process by paying extra for a service.

“They shouldn’t allow people to buy their way around those requirements,” the ACLU’s Stanley said.

CLEAR did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Ticking Clock

Rep. Debbie Lesko (R-Ariz.) the ranking member of the House Homeland Security Transportation and Maritime Security Subcommittee, says she’s developing legislation to mandate that PreCheck, and possibly CLEAR, be accepted as satisfactory credentials. She is also planning to include language that would mandate TSA develop strategies to deal with the overflow of travelers expected to show up starting next October without the right documents. This may include creating a protocol for a more stringent physical screening of those passengers, for example, she said.

Lesko expects the proposal to be finished early next year, with a hearing on the issue to be held then as well.

The election year may actually put pressure for legislation to extend the deadline to pass, Rogers said, as lawmakers up for re-election in November don’t want droves of unhappy travelers among their constituents just weeks before.

“Legislation needs to be done quickly,” Stephanie Gupta, a senior vice president at the American Association of Airport Executives, said in an interview. “You can’t roll out contingency plans on the day the debacle potentially happens.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Michaela Ross in Washington at mross@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Jonathan Nicholson at jnicholson@bgov.com