Pentagon Games Out Climate Change Future While Avoiding the Term

- Coastal planning, databases, and research pinpoint threats

- Military largely mum in public on politically charged issue

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Record-breaking wildfires that spread through central California forced personnel at Travis Air Force Base to evacuate to shelters, relatives’ homes or hotels.

Bases where Marines train recruits and where the Air Force houses its prized fighter aircraft have already sustained billions of dollars in damage from hurricanes. Melting polar ice has triggered showdowns with China and Russia for control of the Arctic.

The Pentagon for years, without fanfare, has been studying how climate change will affect its readiness, where it might spark future conflicts, and how weather will influence extremist activity. Only now, military leaders go out of their way to avoid using the term, wary of crossing President Donald Trump, who has called climate change a Chinese hoax.

The Defense Department’s seeming reticence has rankled some lawmakers.

“I don’t need the Pentagon to weigh into that debate–as to why it’s happened,” said Jim Langevin (D-R.I.), a member of the House Armed Services Committee. “But I do need the Pentagon to acknowledge that it is happening and refer to it as climate change.”

Bases Swamped

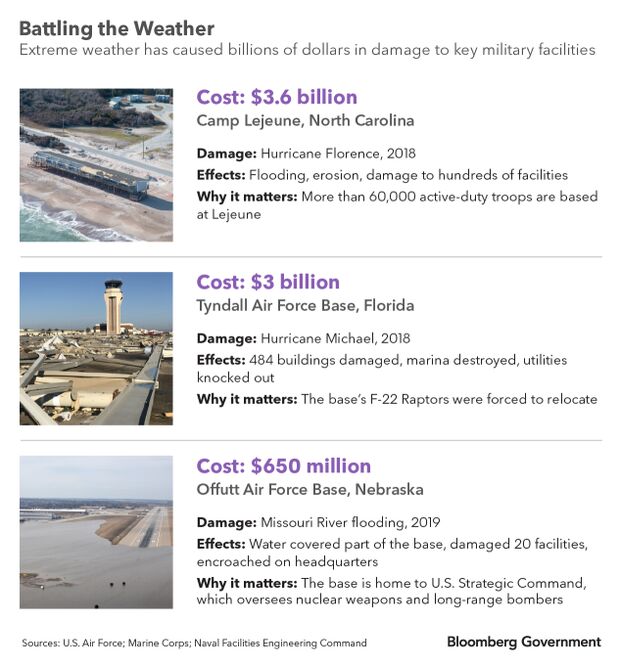

Catastrophic hurricane damage to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida’s panhandle in 2018 was a $3 billion wake-up call to the military. That same year, the Marine Corps’ Camp Lejeune in North Carolina suffered billions in damage from a separate storm and flooding.

Just months later, Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, home to the military command that oversees nuclear weapons and long-range bombers, was inundated by the Missouri River after record snowfalls. Parris Island, one of only two Marine Corps boot camps, and Norfolk Naval Shipyard, which repairs and maintains the Navy fleet, flood frequently as sea-levels rise.

The Pentagon in February ordered all military services to use a new database for planning and construction that tracks projected sea level rise and extreme flooding through 2035, 2065, and 2100, according to an Aug. 31 report to Congress.

That order affects more than 1,700 coastal military sites worldwide.

Though lawmakers had pointedly requested an assessment of “climate change” impacts, the report avoids the phrase except when quoting other materials. The update by Ellen Lord, the under secretary of acquisition and sustainment, does list efforts over the past four years to deal with “extreme weather and changing climate conditions.”

Lord told Congress that the department and all of the services are developing a web-based climate assessment tool that uses federal data and geospatial locating to predict extreme weather, wildfires, and sea-level rise at specific locations.

Meanwhile, defense money is pouring into universities to study how climate change could affect military bases in the Southwest, Pacific, and areas with melting permafrost, according to the report. The Pentagon’s Office of Economic Adjustment is funding local communities that work to prepare for climate threats around bases.

The Pentagon manages more than 4,500 sites and 573,000 buildings around the globe.

China, Russia

Climate change is also a growing challenge for national security strategy as the Pentagon lays plans for global instability, potential future wars, and humanitarian disaster responses.

In the Arctic, rising temperatures are melting ice and opening up competition over natural resources and shipping lanes. Russia is moving to militarize the region and China is increasing its own influence, said Sherri Goodman, a former deputy undersecretary of defense of environmental security and a senior fellow for the environmental change and security program at the Wilson Center.

Russia has put nuclear reactors in the Arctic, is increasing the number of nuclear submarines, and has tested a new nuclear-powered cruise missile there, according to Goodman.

China is expanding influence in the Pacific by promising assistance to island nations that might be inundated by rising seas, which then fall under Beijing’s sway, Goodman said.

“We have to thread our understanding of climate impacts across strategy, which includes policy, plans, programs, but also in the operational sense and tactical level,” she said.

The Pentagon’s Resource Competition, Environmental Security and Stability, or RECESS, program is bringing together about 60 experts from across the department and military services to pool knowledge on how changing environments affect global stability.

“There was an opportunity to connect people who understand the environmental piece with the people in the strategy office and other parts of DOD,” Annalise Blum, a hydrologist with a fellowship in the Pentagon’s office of peacekeeping and stability operations, said. The goal was to “build bridges” and coordinate, she said.

The group weighs the effects of shifting natural environments such as food and water shortages as well as weather, which could include drought conditions driving extremist groups in Africa, for example. But the group isn’t addressing climate change, said Patrick Antonietti, director of the stabilization and peace operations directorate within the deputy assistant secretary of defense for stability and humanitarian affairs office.

“We’re not, you know, climate people,” Antonietti said.

Chinese Hoax

Goodman said Congress has given the department a lot of direction on climate over the past few years but the military hasn’t always been responsive. A Langevin-led congressional push for a list of the top 10 bases threatened by climate change resulted in a 2019 Pentagon report looking at 79 facilities that may or may not face threats, and it included no Marine Corps bases.

“Since the top of this administration thinks climate change is a dirty word, it makes it hard for people who want to examine the real risks to be forthright about them for fear that they might get taken to task for doing the right thing,” she said.

Trump signaled his skepticism of climate change as a candidate, calling it a Chinese hoax. The president has since withdrawn the U.S. from the Paris climate accord, questioned a 2018 federal climate report, and eased greenhouse gas emission regulations. He frequently uses Twitter to contradict or rebuke military leaders.

Republican Opposition

Meanwhile, the Pentagon’s climate change work has drawn criticism in Congress, notably before a House Intelligence Committee hearing in June 2019 in which intelligence community members spoke about the growing threat of climate change to national security.

Mike Conaway (R-Texas), also a senior member of the House Armed Services Committee, expressed skepticism about the link at the hearing and said that he doesn’t agree that the science is settled.

Another Republican, Mark Green of Tennessee, said at an Oversight Committee hearing that same year that preparing for climate change as a matter of national security is a waste of money.

“You cannot call it climate change if you don’t want to and you can probably have the top coverage to do more stuff that way,” said John Conger, the director of the Center for Climate and Security, and a former deputy Pentagon comptroller. “Sometimes you are cognizant of the terminology in order to continue to do the work you need to do to continue your mission.”

The Obama administration wrote climate change into its National Defense Strategy, the military’s guiding priorities. The Trump administration left it out of its update of the strategy in 2018. It was “less like somebody put their foot on the brake and more like they took their foot off the accelerator” over the past three years, Conger said.

Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has said he will make climate change a top priority if elected.

“The right question is how does climate change affect Russian behavior or Chinese behavior and by understanding this part of the problem how can we anticipate what they’re going to do,” Conger said. “You will hear people in a future administration, if it comes to pass, talking about that more.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Travis J. Tritten at ttritten@bgov.com; Roxana Tiron in Washington at rtiron@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.