Virus Job Losses, Evictions Seen Risking Mass Attacks in Future

By Shaun Courtney

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The coronavirus, already at the root of shutdowns and job losses that have crippled the nation’s economy, poses another potential risk: contributing to deadly mass attacks when businesses, schools, and concerts reopen.

“There are a lot of struggles and circumstances that people are facing right now,” Steven Driscoll, supervisor social science research specialist for the U.S. Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center, told reporters in a call about Covid-19’s potential impact on mass public attacks.

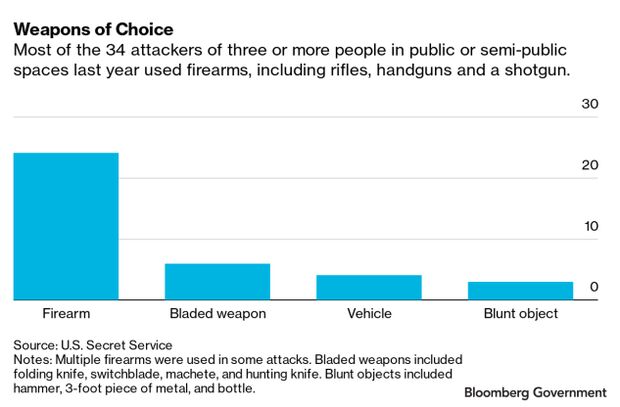

In 2019 there were 34 attacks—gun-involved and not—in which three or more people were injured or killed in a public space in the U.S., the Secret Service reported. More than 80% of the 2019 public attackers experienced stress, such as financial instability, homelessness, job loss, domestic violence, or personal relationship problems during the year before their attack.

Anxiety about the pandemic and continued shutdowns may tamp down public fears of mass attacks in public spaces when the economy reopens, said Jillian Peterson, an assistant professor of criminology and criminal justice at Hamline University in Minnesota and co-founder of the Violence Project.

“The other line of thinking, which I think to me is more likely and more concerning, is that all of the risk factors that we know of are really being amplified right now,” she said.

Perfect Storm

The Secret Service report found several common features among the experiences and stresses of attackers who carried out the 34 mass public attacks in 2019. Many attackers had lost their jobs, used or abused substances, displayed mental health problems, or had other recent stressful events. They often had prior criminal charges or a history of arrests or domestic violence.

About one-third of the 2019 attackers were retaliating for “perceived wrongs,” with about a quarter of them reacting to personal grievances “such as an ongoing feud with neighbors, being kicked out of a retail establishment, being teased or bullied, facing an impending eviction, or being angered and frustrated about college debt and job prospects,” the Secret Service’s Aug. 6 report said.

These factors alone don’t mean someone will become violent, but can be pieces of a puzzle that contribute to an attack, especially when the person has a history of violence, arrests, or mental health struggles, the agency reported.

Almost 13 million fewer people were employed in July than in February, the latest Labor Department jobs report showed. More Americans are facing job losses, and limited action by the president on unemployment benefits and evictions is unlikely to stem a wave of mortgage defaults, missed rents, and financial strife. Congressional talks on another relief package are at a standstill.

“People are super stressed right now; hopeless depression and suicidality is up. Also, people are spending more and more hours on the internet, which is not good for some people,” Peterson said. “We also know that gun sales are up. So if you put all of those factors together, it could be really a perfect storm.”

Almost 3 million more firearms were sold in the U.S. than would have ordinarily been sold between March and mid-July, according to a Brookings Institution report. The calculations were based on the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System, which is closely correlated with firearm sales. NICS initiated more than 3.9 million background checks in June 2020 alone—the most in the system’s history.

`Social Contagion’

So far in 2020 there has been one attack comparable to the ones the Secret Service studied in 2019—at a Molson Coors facility in Milwaukee in February. By mid-March, stay-at-home orders and social distancing left far fewer crowded public places to attack.

“You don’t have large crowds of people gathering together— you don’t have concerts, you don’t have crowded restaurants, you don’t have crowded churches. You don’t certainly have schools open until now,” said James Alan Fox, professor of Criminology, Law and Public Policy at Northeastern University and author of the 2019 book, Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder.

Mass killings have a contagious effect because the public tends to obsess over them. They’re discussed among neighbors, in political debates, and on the news—and that gives people the idea to channel their anger or grievances with an attack, both Fox and Peterson said.

“It’s our fear obsession that keeps that notion alive. If we get distracted from it and turn our attention to other things that social contagion can disappear,” Fox said.

Both Fox and Peterson point to the change in the rate of school shootings before and after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, as a possibility of what might come after the pandemic. From 1995 to 2001, there were eight multiple-victim school shootings, but after Sept. 11 there were no such attacks for four years, as Americans turned their attention to the threat of terrorism, Fox said.

“I’m hoping that even as things eventually open up that we won’t have this contagion. They won’t be eliminated—it will go back to perhaps where we were before we’re about five orsix public mass killings a year, as opposed to 10,” Fox said.

Mental Health

“We’re paying so much attention to our physical health and how to protect ourselves physically which is hugely important, but I think we have to be also talking just as much about mental health, and how to be looking for signs of a crisis, how to be checking in on people,” Peterson said.

The Secret Service presented its findings with more than 11,000 stakeholders such as school personnel, law enforcement, mental health professionals, and venue managers when it released the report last week, Justine Whelan, a public affairs officer for the agency, said.

Those groups should work with their relevant public safety partners to keep their communities connected by “facilitating safe returns to the workplaces or to schools, and also taking steps to address and support those personal stressors that may come with the current circumstances, including things like the financial instability, mortgage defaults, losing jobs,” the Secret Service’s Driscoll said.

“All of us have more of a role to play in this than we think,” Peterson said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Shaun Courtney in Washington at scourtney@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com; Sarah Babbage at sbabbage@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.