US Facing Crisis in GPS Workforce With China Poised to Dominate

By Jack Fitzpatrick

- US officials, academics warn of ‘geodesy crisis’

- Government scientist wants ‘national thrust’ in education

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Ukrainian soldiers using American-made rocket launchers have to contend with Russian attempts to jam their satellite-guided signals, a battlefield challenge that emerging science will soon address.

But who will own that technological advantage is an open question.

Listen to Jack Fitzpatrick talk about this story on our weekly podcast.

The future of precision missiles, as well as drones, driverless cars, super-precise synchronized clocks, and navigation of the Moon and Mars, depends on a specialized science called geodesy, a field Americans dominated a generation ago — but have almost entirely abandoned.

And it’s a science China has embraced.

“There’s a real economic advantage, I would submit, and a national advantage to being that source for positioning, navigation, and timing,” said Nikki Markiel, the top geomatics scientist at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), a combat support agency within the Defense Department.

The next generation of GPS-like technology will likely be based on hundreds of low-hanging satellites whose signals are nearly impossible to jam. Advances will be built on geodesy’s study of the Earth’s shape, positioning in space, and gravitational field.

About 20 Americans graduated with a master’s degree or Ph.D. in geodesy in the last decade; in some adversarial nations such as China, that number is roughly 1,500, according to Markiel.

“Banking, finance, Wall Street, oil and gas, time transfers, telecommunications — are all getting their timing from our GPS,” Markiel said. “Envision a world where someone else becomes that preeminent source. That has major implications in terms of global geopolitics.”

The US geodesy brain drain is forcing federal agencies to scramble to train mathematicians and causing academics to wonder who will teach classes when the remaining US geodesists retire.

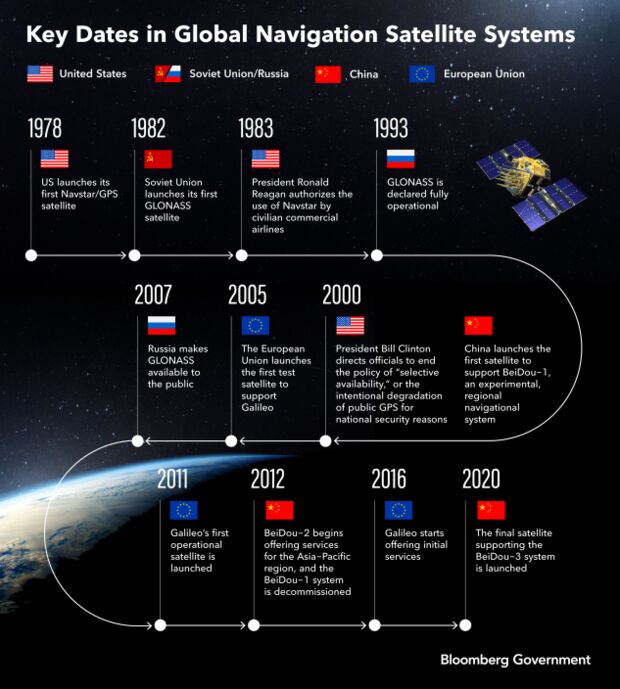

And the aging of America’s geodesists raises the possibility of the Pentagon-created Global Positioning System being surpassed by its competitors, including China’s BeiDou and the European Union’s Galileo. It also means future advances in driverless cars, drones, precision agriculture, and super-fast Wall Street transactions could come from other countries.

‘Nonexistent Expertise’

“Geodesy is an essentially nonexistent expertise in the United States, while other countries invest quite heavily in the foundational and applied sciences,” said Dorota Grejner-Brzezinska, an Ohio State University professor who’s a member of the National Science Board. “Putting more research and development funding to train geodesists is absolutely needed.”

Launched in the 1970s by the US Department of Defense, GPS was — and remains — a network of a few dozen satellites orbiting about 11,000 miles above the Earth. The government opened the system to civilian use in the 1980s, revolutionizing how we travel. But over the last few decades, the US let slip its virtual monopoly on the science underpinning position, navigation, and timing.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan took the Pentagon’s focus away from the fundamental science of geodesy, Markiel said. As demand waned for geodesists, universities closed down their programs.

Now, NGA — which collects satellite images for national security — struggles to hire geodesists. The agency instead focuses on “hiring smart people with degrees in things like mathematics or physics, and then spending a number of years” training them in geodesy, Markiel said.

Federal agencies typically can’t hire non-citizens, and the NGA is “more constrained than others,” often requiring security clearances, Markiel said.

China Competition

Wuhan, China, has become “the single biggest center of geodetic research in the world,” a group of academics and former federal employees wrote in a January 2022 white paper titled “The Geodesy Crisis.” More geodesy graduate students are educated in Wuhan than in the entire US, the paper says. “China has been out-training the rest of the world in geodesy for about 15 years,” it adds.

Michael Bevis, an Ohio State University professor who led the white paper, said it’s possible the US is already past the point of no return and can’t catch up to China and European competitors.

“I think we will be permanently disadvantaged and that China and Germany will be permanently more advanced,” Bevis said in an interview.

Grejner-Brzezinska similarly warned the US “can maintain primacy” of GPS over BeiDou and Galileo “for some time, but we may lose it soon.”

Driverless Cars, Cat Videos

GPS, or its competitors, could become far more reliable and less susceptible to jamming and spoofing, if scientists work on further advancements. That would be particularly relevant in future military conflicts, said Richard Salman, a former director of NGA’s Office of Geomatics.

“Everybody knows you can jam GPS really easily,” Salman said. “In a real conflict, GPS may be taken out to some degree.”

Small, “low-Earth orbit” satellites, like SpaceX’s Starlink constellation, could be key in setting up a GPS replacement that’s more difficult to jam, Bevis said, adding that could be possible in the next 15 to 20 years.

Geodesy is also critical in the race to develop the best real-time navigation. Driverless cars can’t currently rely on GPS because it’s not precise enough. Military navigation applications — which “don’t have the luxury of nice, white lines on the freeway” — face even bigger challenges, Markiel said.

Even the basic tenets of geodesy will be needed to eventually create a reference frame for the shape and gravitational field of the moon and Mars, Salman said.

Telecommunications technology also stands to gain, as scientists improve their ability to precisely synchronize clocks, Markiel said.

“That goes into all of those aspects of faster 5G, faster microwave, faster cat videos on YouTube,” she said.

‘Big Problems to Solve’

University research funding is a key to rebuilding the US community of geodesists, Markiel said, noting it’s “an inherent government function” that won’t be supplanted by the private sector.

“We need to really seriously look at, if you will, an Apollo program,” Markiel said. “We need to have a really major national thrust to say, ‘We have big problems to solve, and they’re going to require all kinds of unique research.’”

The National Geospatial Advisory Committee, a panel sponsored by the Interior Department, agreed to a resolution in December 2022 calling for “an ambitious program of educational support, research funding, and government agency action” to address the shortage of American geodesists.

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy should lead an all-of-government approach on the issue, Salman and Bevis said.

In November 2022, members of the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Advisory Board — which advises the federal government — agreed “funding should be increased to enhance PNT Research & Development, including Geodesy, and to strengthen education and training,” according to recommendations sent to officials at the departments of Defense and Transportation.

Grejner-Brzezinska, a member of the PNT Advisory Board, said the US doesn’t need to match China’s number of geodesy degrees, but it should try to get back to the levels Americans saw in the 1990s, when Ohio State University had about 90 to 95 students studying geodesy at a given time.

“We don’t need thousands and thousands of geodesists,” she said. “But we still need them.”

Staying ‘Globally Competitive’

Some federal officials, including those at NGA, understand the problem, but it hasn’t been addressed at the highest levels of government. Congress, which controls government spending, could tackle the issue if lawmakers recognized it, according to Salman.

“I don’t know what congressman out there gives a crap,” he said.

At least one committee in Congress is paying attention. Nora Kohli, communications director for Democrats on the House Intelligence Committee, told Bloomberg Government, “A national scarcity of geodesists could threaten critical Intelligence Community missions, particularly those undertaken by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.”

“The House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence fully supports efforts to expand awareness of and training in this critical discipline, and is committed to working with existing experts in the field to ensure our geospatial development remains globally competitive,” she said in a statement.

NGA has taken some steps on university funding recently, but not as much as academics sought. The agency announced last year Ohio State would get $28.5 million over three years to lead a multi-university consortium on geomatics and applied sciences, which could be renewed. That falls short of a more ambitious plan Bevis and Salman pitched for a University Affiliated Research Center tied to NGA. Bevis said he “could imagine a $100 million UARC” but said that style of Pentagon research partnerships with universities “have gone out of favor.”

‘Slowly Starving to Death’

Domestic agencies also are struggling to hire geodesists, raising concerns about natural disaster preparedness and response.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration “is having a hard time finding qualified applicants,” Juliana Blackwell, director of the National Geodetic Survey, said in an email. “We often send employees back to school to get advanced education to do the job we hired them to do, so that we can accomplish our mission.”

The National Geodetic Survey can’t do much because it’s tucked within NOAA’s National Ocean Service and doesn’t control its own funding, Bevis said. The office should be turned into its own “funding office” on par with the National Weather Service, but instead it’s been treated like “a medieval prisoner chained to the wall in a castle, slowly starving to death,” Bevis said.

David B. Zilkoski, a former NGS director, also said university grants could be a solution but NGS doesn’t have the budget.

“Grants to universities would be a major push that would be very, very important,” Zilkoski said. “NGS has limited funds to do either of those — grants or hire people.”

The Department of Agriculture has also been slow to respond, said Everett Hinkley, a program manager at the US Forest Service’s Geospatial Management Office, who’s worked on efforts to improve wildfire detection using satellite imagery. Agencies that rely on mapping are “going to start to see things falling off in terms of our positional accuracy,” Hinkley noted.

“I have trouble getting anyone’s attention on this at USDA,” Hinkley said in an interview. “I’m like Chicken Little saying, ‘Hey, look, we have to pay attention to this. We need an all-of-government approach.’”

The academic community is nearing a tipping point as many trained geodesists retire. “It raises the question, who’s going to do the teaching?” said Zilkoski, who retired from NGS in 2009 and now writes for GPS World magazine.

That’s caused agencies like NGA to rely on short-term fixes. Salman retired as director of the agency’s Office of Geomatics in 2020 but is going back to work as an adviser, “probably part time,” he said. “I don’t want to work full time.”

“I’m 72 years old,” Salman said. “And as I look at this, it’s very sad to watch.”

Jonathan Hurtarte also contributed to this story.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jack Fitzpatrick in Washington at jfitzpatrick@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com; Giuseppe Macri at gmacri@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.