Thoroughbred Deaths Cast Cloud on Racing Ahead of Kentucky Derby

By Teaganne Finn

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

- Rash of thoroughbred deaths pressuring Congress to intervene

- Industry faces growing questions about treatment of racehorses

The Kentucky Derby—American horseracing’s biggest event—will be run Saturday amid mounting concern about a rash of recent thoroughbred deaths that is increasing pressure on Congress to pass uniform nationwide anti-doping standards and testing.

Similar legislation, which would also ban raceday drugging that some veterinarians and animal-rights advocates tie to fatal injuries, never gained much traction in past sessions, despite bipartisan support. Sponsors think the recent attention on racehorse deaths will generate fresh momentum in the current Congress.

“Discerning fans are growing in numbers and if we don’t strengthen the industry it’s at risk,” said sponsor Paul Tonko (D-N.Y.), whose district includes Saratoga Springs and its famed track.

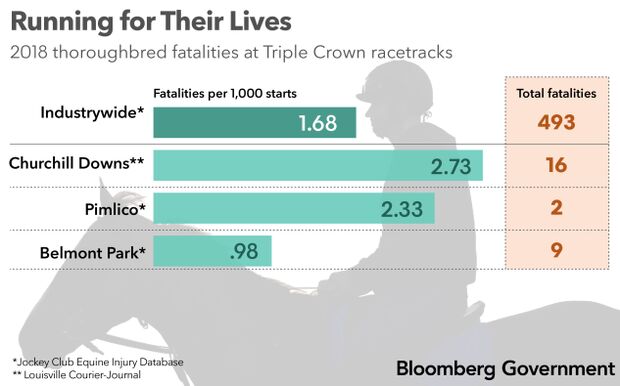

The 145th “Run for the Roses” comes at a precarious moment for U.S. racing. The deaths of 23 racehorses earlier this year at California’s Santa Anita racetrack followed 493 thoroughbred deaths at American racetracks in 2018, according to the Jockey Club Equine Injury Database. Sixteen of those deaths occurred at Churchill Downs, site of the Kentucky Derby, the Louisville Courier-Journal reported in March.

Public concern about the treatment of animals has already led to the demise of the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus, a referendum last year to outlaw greyhound racing in Florida, and Seaworld Entertainment Inc.‘s 2016 decision to end captive breeding of Orca whales. The horseracing industry fears it could suffer a similar fate absent public confidence that racehorses are humanely treated.

“There’s a desperate need for federal regulations. The current system does not work and everyone knows it doesn’t work and everyone is just in denial,” Jeff Gural, CEO & chairman of Meadowlands Racing & Entertainment in New Jersey, said in an interview.“No question in my mind horseracing has a major problem. The system we have is completely broken and hopefully the federal government will get involved.”

“I think it’s at a crossroads,” he added. “The number of people who have signed on federal legislation is growing. Just a handful of veterinarians are in denial.”

Regulatory Patchwork

The Horseracing Integrity Act of 2019 (H.R. 1754) would replace a patchwork of state racing standards enforced by 38 separate state regulatory agencies with a uniform anti-doping and medication control program that the United States Anti-Doping Agency would be charged with developing and enforcing. It also would ban the use of all medications within 24 hours of a race.

“Until we’re at a place with national uniformity where we do have enhanced safety, we need the legislation,” original cosponsor Andy Barr (R-Ky.), whose state hosts the Kentucky Derby, said in an interview.

The bill is backed by animal welfare groups, a variety of horseracing industry interests including the operators of several major racetracks and breeders’ organizations, and the Jockey Club, which helped write the legislation and is one of the most influential industry organizations in horse racing. There are 64 bill cosponsors.

“The sooner Congress can implement legislation and get it uniform across the country, you likely won’t see significant breakdowns,” said Kitty Block, president and chief executive officer of the Humane Society of the United States.

Raceday Doping

Among the drugs that would be banned from race-day use is furosemide, or Lasix, a diuretic widely administered by U.S. trainers to alleviate bleeding from the lungs during races. Critics say raceday use of the drug, which is widely banned internationally, causes dehydration that endangers the horses by making them susceptible to muscle failure and collapse.

Block called same-day drugging a “huge contributor” to horse injuries and fatalities.

“You can see the direct line of whether or not a horse has been drugged,” she said.

The drug is also viewed as a performance enhancer.

A 1999 peer-reviewed study in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association that analyzed 22,589 race records found “horses that received furosemide raced faster, earned more money, and were more likely to win or finish in the top 3 positions than horses that did not.”

Defenders say the drug is administered to protect the animals. Lasix’s therapeutic purpose is to prevent bleeding from the lungs, which is called exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage.

Lasix is “completely irrelevant” to the horse fatalities at Santa Anita, said Dr. Clara Fenger, a board member of the North American Association of Racetrack Veterinarians and opponent of the bill.

“It’s the opposite — the drug is linked to prevention of deaths,” said Fenger, a veterinarian in Kentucky.

Across the Pond

Most countries outside North America don’t allow Lasix. Japan, Australia, the United Kingdom, and others permit Lasix during training but prohibit it on race days. In Germany, Lasix is prohibited at all times.

Earlier this month, the Grand National, a National Hunt horse race held in England, suffered its first three horse deaths since 2012.

U.S. horseracing “lags” behind international standards to combat doping, the Jockey Club said in a statement.

“Based on amalgamated data from various sources, our horse injury rates are 2.5 to 5 times greater than the rest of the world,” the Jockey Club said.

Better Outlook

Most recently, Churchill Downs joined a coalition of racetracks seeking to ban raceday medication for all of their 2-year-old races beginning next year. Beginning in 2021, the same prohibition would extend to all horses participating in any stakes race at coalition tracks.

Churchill Downs has “always opposed my legislation,” said Barr, who described the track operators’ stance as a “very important change of position.”

Participants in the coalition include all of the racetracks owned and operated by Churchill Downs Inc., the New York Racing Association Inc., and The Stronach Group, which operates Santa Anita. Churchill Downs spent $60,000 lobbying Congress in the first quarter of 2019 on various issues, including the Horseracing Integrity Act, according to lobbying disclosure filings.

The House legislation would go beyond the coalition’s position, establishing a standardized list of permitted and prohibited substances, treatments and methods for all covered races in the United States.

Tonko said the focus on racehorse safety enhances his bill’s prospects this year. “Absolutely,” he said. “I think it’s drawn a lot of attention to the issue.”

Chauncey Morris, executive director of Kentucky Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders, said the industry will “have to adapt if we want to thrive.”

“Customers, they vote with their feet if we don’t adapt and change,” he said.

Dr. Mary Scollay, equine medical director at the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission, which hasn’t taken a position on the bill, said horseracing is “on the cusp right now.”

“If we cannot improve stewardship of horses and can’t convince the general public we really do care and want them healthy and happy, enjoying what they do, I think our days are numbered,” she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Teaganne Finn in Washington at tfinn@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Jonathan Nicholson at jnicholson@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.