Swing-District Lawmakers Keep It Local to Bypass ‘Crazy Town’

By Zach C. Cohen

- Vulnerable members focus on infrastructure, crime, farm issues

- Presidential politics may override parochial campaign strategy

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The port needed Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez’s help.

Driving in a white van along the Columbia River that separates her home state of Washington from Oregon, executives from the Port of Vancouver showed the first-term Democrat how the aging docks shipping wheat and wind turbines needed tens of millions of dollars in improvements.

They knew they had an ally in Gluesenkamp Perez, who had petitioned Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg for a federal maritime infrastructure grant and secured half a million dollars in earmarks in a committee-approved funding bill to expand or improve the century-old docks.

“People do not care about most of the bills that we’re passing in Congress,” Gluesenkamp Perez said in an interview at the port. “They care about effectively delivering better government that’s relevant to the things people are experiencing.”

Lawmakers such as Gluesenkamp Perez from competitive districts are honing in on local bread-and-butter items as they seek to distance themselves from the overheated and polarizing rhetoric that consumes Washington, D.C., but often alienates more independent voters who they will need to get re-elected next year.

Trump-District Democrat Selective About Party-Line Voting

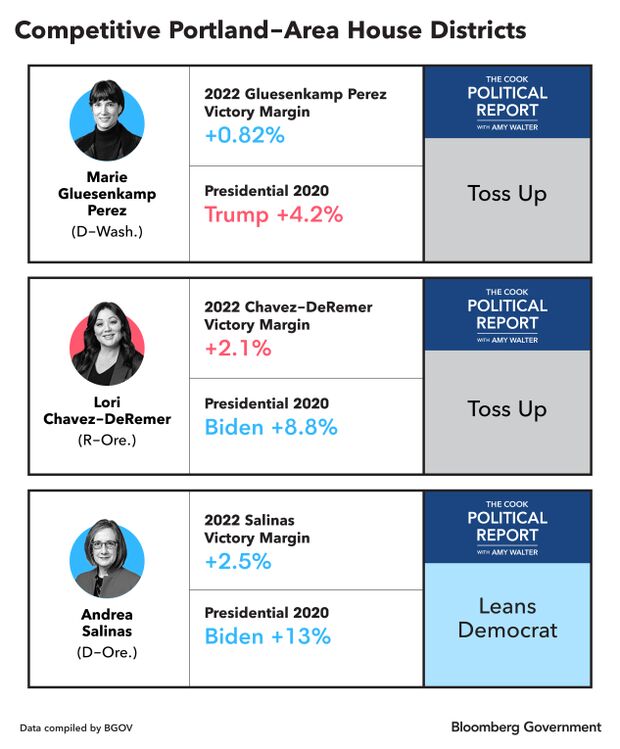

The ability of these swing-district lawmakers, including several in the Pacific Northwest, to thread that needle will determine which party will win the majority in 2024.

They’re embracing the “all politics is local” strategy popularized by former Speaker Tip O’Neill (D-Mass.), who presided over the House during a less partisan era in the 1970s and 1980s.

“When you’re in a swingy district, you want your personality and your character to be defining the race, not the label,” said Mike Zamore, who teaches at American University’s Washington College of Law and was a chief of staff to Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.).

That approach, however, will be tested in 2024, when the presidential race will heavily drive voters’ perceptions and turnout and at a time when party-line voting is becoming the norm. Former Rep. Tom Davis (R-Va.), who led the National Republican Congressional Committee during the 2000 and 2002 cycles, said voters’ increasing penchant for voting for the party rather than the candidate makes it harder for lawmakers to substantially distance themselves from the top of the ticket.

Just 23 of the House’s 435 seats today are held by a member of the party representing a district that favored the other party’s presidential nominee in 2020.

The local approach “can make a difference in two or three points because of the people you help,” Davis said. “But it’s pretty tough.”

‘Staying Out of Crazy Town’

Gluesenkamp Perez’s rural district, bounded by the Cascades and the Pacific Ocean, is home to many fiscal conservatives who pay no personal income tax in Washington or sales tax when shopping in Oregon.

In 2022, she bested Joe Kent who had defeated GOP incumbent Jaime Herrera Beutler after she voted to impeach former President Donald Trump for “incitement of insurrection” through his efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

Kent is running again in the district that backed Trump in 2020, in part by opposing proposals to build light rail across the Interstate 5 bridge frequently clogged by commuters between Vancouver, Wash., and Portland. Leslie Lewallen (R), who is on the city council of the Portland suburb of Camas, Wash., is also running in the nonpartisan primary that will send two candidates to the general election.

Gluesenkamp Perez is banking she can beat Kent again by “staying out of crazy town” and highlighting his questioning of the 2020 election, support for limiting legal immigration, and suggesting that infectious diseases expert Anthony Fauci, who led the effort to respond to Covid-19, should be charged with “murder.”

“Those are things I don’t think are top priorities or core beliefs of almost anyone in my district,” Gluesenkamp Perez said.

Kent’s campaign didn’t provide a comment but in a June statement said Gluesenkamp Perez’s record in Congress “is that of an out-of-touch extremist.”

Homelessness and Crime

The three competitive House districts near Portland will be among those races in which candidates of both parties will be trying to keep their attention on parochial matters. Elsewhere in the country, Republicans are also seeking to hang on to Democratic-leaning New York districts they won in 2022 by emphasizing local concerns.

Republicans preparing to run in these districts will in particular focus on homelessness and crime, which has received much media attention in both Portland and New York City.

“Our candidates are focused on those issues,” said NRCC Chairman Richard Hudson (N.C.).

Rep. Lori Chavez-DeRemer’s (R-Ore.) district, which stretches from the Portland suburbs to Bend, more than 150 miles away, is among the most competitive in the country. She beat her Democratic opponent, Jamie McLeod-Skinner, by fewer than 7,300 votes two years after the district backed President Joe Biden by nearly 9 points.

Chavez-DeRemer spent the early days of August recess meeting with voters from Clackamas County, a political battleground that split its votes for Senate and governor last fall. After touring an egg farm in Canby, she worked her way to a picnic for Milwaukie, Ore.-based grains producer Bob’s Red Mill Natural Foods Inc.

She spoke with its leaders about legislation she supports easing such small business owners’ path to transferring ownership of their companies to their employees (H.R. 3383).

Chavez-DeRemer said she won last year’s race because voters wanted their representative to tackle crime, support education, and foster a good local economy.

“People wanted to address specific issues,” she said in an interview. “Those were local issues, not national issues.”

McLeod-Skinner, who had unseated the more moderate Rep. Kurt Schrader in last year’s Democratic primary and is running again, wants to tie Chavez-DeRemer to national politics and what her consultant Annika Albrecht said was the “the MAGA extremist agenda” of the Republican Party.

Janelle Bynum, a Portland-area state legislator who is also seeking the Democratic nomination, likewise accused Chavez-DeRemer of an “alignment with the extreme.” She criticized the incumbent for voting for House Republicans’ version of the annual military policy bill (H.R. 2670) that would block the Pentagon from helping troops travel out of state to obtain abortions.

Abortion Bills Paused as GOP Moderates Try to Win Back Women

Chavez-DeRemer, who generally opposes her party’s push to expand the federal restriction on funding abortion, dismissed any attempts by Democrats to link her with the more controversial stands of her party. “My job is to keep my head down, work hard for my constituents,” she said.

Bucking Party

The parties are also keeping an eye on re-election races of two first-term Democrats in Oregon: Reps. Andrea Salinas and Val Hoyle. Salinas represents the state’s newest congressional district, which runs through the Willamette Valley toward the state capital of Salem. Hoyle occupies a coastal seat anchored in the college town of Eugene.

Salinas, who represents a district that Biden would have won by 13 points, rarely bucks her party. When she does, it’s often on crime policy.

She voted with Republicans to retain the Drug Enforcement Administration’s ability to crack down on fentanyl distribution (H.R. 467), make assault of law enforcement worthy of deportation (H.R. 2494), and to reject a D.C. law overhauling the city’s criminal code (Public Law 118-1).

“We have to listen to rural and suburban and urban to get anything done,” Salinas said in an interview in the Portland suburb of Sherwood during National Night Out, an annual party convening police officers and the rest of the community. Salinas, the daughter of a San Francisco police officer, shortly after arriving at the party put on a sticker in the shape of a police shield designating her “Jr. Police.”

Salinas said members of both parties need to push back on their most ideologically extreme elements but anticipated that on the airwaves, “the rhetoric is going to be extreme all the time,” she said.

— With data visualization from Jonathan Hurtarte.

To contact the reporter on this story: Zach C. Cohen in Portland, Ore., at zcohen@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com; Loren Duggan at lduggan@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.