Stoking of Pre-Uber ‘Dark Ages’ Drives California Ballot Message

By Tiffany Stecker

- Ballot measure backed by Uber, Lyft has record $185 million

- Opponents’ campaign focused on gig workers’ labor rights

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Remember what it was like to wait for a taxi? Enter yet another cab with a broken credit card machine? Pick up your own restaurant takeout?

It was barely a decade ago, but memories of a world before Uber seem distant for most Americans. Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. revolutionized local road travel, giving riders a cheap, fast, and comfortable alternative to taxicabs by tapping a smart phone app, while DoorDash Inc., Instacart Inc., and Postmates Inc. popularized deliveries of takeout meals and groceries to your door.

The threat of going without those conveniences is being sold to California voters as part of a record $185 million campaign financed by the gig-economy giants in support of a Nov. 3 general election ballot initiative (Proposition 22). It would preserve the contractor business model central to their success and exclude them from the state law known as Assembly Bill 5.

The companies’ pitch is “we’ll be back to the dark ages of having to call a cab” if the measure fails, said Thad Kousser, a politics professor at the University of California, San Diego.

The Yes on 22 campaign raised that possibility in a television ad that ran in August and September. The new law “could eliminate hundreds of thousands of jobs by making it illegal for app-based drivers to continue working as independent contractors, threatening to shut down rideshare services across California,” the ad’s announcer said.

So far, it appears to be working. Recent polling suggests Californians hold tight to their rideshare, restaurant delivery, and grocery shopping services, and a majority think the drivers should have the freedom of an independent contractor rather than the protections of an employee. More than half, 55%, responded in a poll last month that they would be at least somewhat affected if Uber and Lyft no longer operated in California.

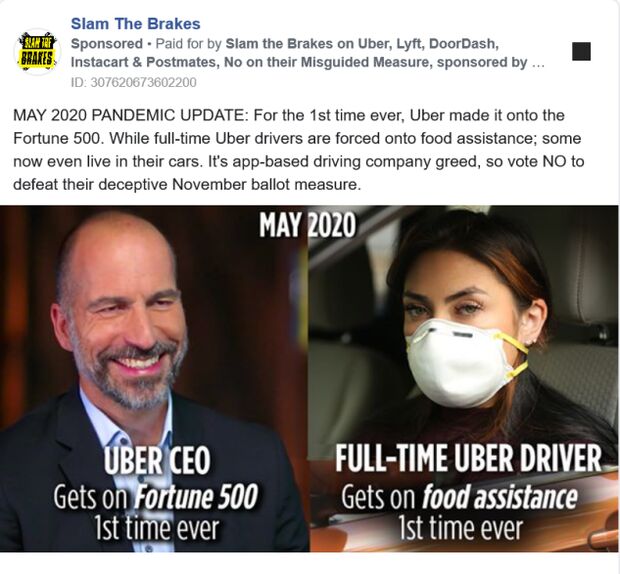

But many voters remain undecided, and opponents are mounting a grassroots campaign to counter claims that the proposal is good for drivers and the public. The “Slam the Brakes” campaign against Proposition 22, running on less than one-tenth of the Yes campaign’s budget, released its first television spot Thursday.

“The people who are suffering the most right now, in the middle of a pandemic and a racial reckoning, are the ones who are going to lose the most if this initiative passes,” said Chris Melody Fields Figueredo, executive director of the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, which provides support to the Proposition 22 opposition campaign.

Independent, With Benefits

California Democrats and labor unions say the convenience that made on-demand apps so popular comes at a cost: rock-bottom wages for drivers, no worker protections, and at least $413 million that wasn’t paid into the state’s Unemployment Insurance Fund because the companies don’t consider the workers employees, according to a University of California, Berkeley analysis. The Democratic-controlled Legislature passed A.B. 5 last year to stop companies from sidestepping the state’s labor laws by classifying workers as contractors.

UC Berkeley’s Institute of Government Studies poll of 7,198 registered voters in mid-September found likely voters almost evenly divided. Among respondents, 39% said they would vote yes, 36% no, and 25% were undecided.

Proposition 22 reflects a compromise offered by the gig companies themselves. It allows current and future app-based platforms to keep using independent contractors while providing the workers with new benefits and protections.

The proposal would require them to pay drivers at least 120% of the hourly minimum wage, plus 30 cents per mile to defray expenses, from the moment when a driver accepts a ride request to the completion of the trip.

.

The initiative also directs the companies to subsidize a portion of their workers’ health plans, insure drivers for on-the-job accidents, and protect drivers and riders against discrimination and sexual harassment.

Earlier: Nine-Figure Campaign By Gig-Worker Users Can Move Into High Gear

Uber and Lyft have been battling in court to avoid complying with the new law. It went into effect this past January, cementing a standard that makes it practically impossible for the ride-hailing companies to classify drivers as independent contractors. The companies in August threatened to leave the state after a judge ordered the companies to comply, but backed down after a court put the order on hold while the companies appeal the decision.

The Yes on 22 campaign has spent over $65 million this year to blanket the state with television, cable, radio, and digital ads, according to the political ad tracking service Advertising Analytics.

Those ads spotlight people who drive as a side hustle in between raising children, caring for elderly relatives, going to school, and working other jobs.

53% in Favor

With less than five weeks to go before Election Day, a Redfield & Winton Strategies poll of 2,000 registered voters found that 53% likely voters would vote yes on the measure, and 27% would vote no, with 20% unsure. The margin of error was 2.2%.

The majority support for Proposition 22 is likely linked to consumers’ positive view of the companies, the pollsters said. Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart, and Postmates all held strong net favorability ratings. Roughly a quarter said they use Uber and Lyft at least once a month, and almost one-third use DoorDash for food delivery at least once a month.

But would the companies actually leave? Stephen Levy, an economist and director of the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy, doesn’t think so.

“There’s room for them to increase prices and maintain most of their business,” Levy said. “I think they’re bluffing.”

If the rideshare platforms get their way and succeed in passing the measure, they would raise prices anyway to cover the new benefits, said Levy, who is not affiliated with either side of the Proposition 22 fight.

To counter the money and influence Uber and Lyft have put behind the campaign, opponents are relying on labor unions’ reach and influence to relay their message, Slam the Brakes spokesman Mike Roth said.

Each of California’s 2.5 million union members will be reached six to eight times by phone or text message, Roth said.

“The person-to-person contact is the gold standard,” he said. “No one does it better than labor.”

‘Second Class’

By not classifying more than 1 million drivers as employees, the companies wouldn’t be required to pay for unemployment insurance, paid sick leave, or worker’s compensation—benefits that many more Californians rely on during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The minimum wage wouldn’t cover time spent waiting for ride demand, opponents say. And the measure’s travel expense reimbursement rate is lower than the IRS’s 57.5 cents-per-mile rate.

Any changes to the measure if it passes would require a seven-eighths majority vote in the California Legislature.

“It essentially creates a second class of workers,” Figueredo said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Tiffany Stecker in Sacramento, Calif. at tstecker@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Tina May at tmay@bloomberglaw.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.