Rotisserie Chicken With Food Stamps? Lift the Ban, Lawmakers Say

By Maeve Sheehey

- Costco, Walmart among top sellers of rotisserie chicken

- SNAP benefits can’t be used on hot and prepared foods

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Anti-hunger advocates are asking Congress to revisit a food stamp rule dating back half a century that keeps recipients from paying for hot foods with their government benefits.

The Agriculture Department’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, meant to help people purchase food if their income falls below a certain threshold, reached more than 1 in 10 Americans last year, with its ranks swelling since the Covid pandemic exacerbated food insecurity.

But proponents argue the program hasn’t adjusted to Americans’ changing food habits since the 1970s, when lawmakers sought to limit the SNAP recipients from purchasing from fast food joints like Kentucky Fried Chicken. As part of SNAP’s five-year reauthorization in the 2023 farm bill, members of Congress from both parties want that rule changed.

The debate highlights just how hard it is to rewrite the largest food assistance program in the U.S., playing into broader partisan division over what some Republicans view as an expansion of welfare that could open the door to purchases far beyond grocery stores.

“The fact that you can use SNAP to purchase a frozen, breaded chicken, but not a hot rotisserie chicken or a salad from a grocery store salad bar, frankly, makes no sense,” Rep. Bobby Rush (D-Ill.), said in a statement.

Rotisserie chicken is a popular dinner staple because it can be purchased for as little as $6 at the grocery store—roughly the same price as an uncooked chicken—and doesn’t require prep work.

Costco Wholesale Corp. is the largest seller of rotisserie chickens, followed by chains such as Walmart Inc., the Kroger Co., and ShopRite.

Proponents of the rule argue that rewriting or striking it could open the door to restaurant purchases, which isn’t what the program was originally meant to be.

Rep. Abigail Spanberger brought the topic to the table at an early farm bill hearing on the program last month. “I’m especially interested in examining the ways that we can improve flexibilities for those who rely on SNAP to put food on the table,” the Virginia Democrat said, advocating a bill from Rush (H.R. 6338) that would strike the rule.

“I don’t have a problem with a rotisserie chicken being available as part of the program,” Rep. Austin Scott (R-Ga.), said. “I do have a problem with a happy meal or a drive-thru being part of it, and I don’t understand why we can’t have an honest discussion about obesity with our youth and in what is available to be purchased with SNAP benefits.”

The congressman questioned why the program can’t move in the direction of the more restrictive Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, or WIC, which specifies that recipients must buy food with nutritional value.

The Ins and Outs of SNAP

Ellen Vollinger, the SNAP director at the nonprofit advocacy group Food Research & Action Center, said grocery stores have changed—and with them, the way Americans shop. Prepared meat and fish are more common purchases, she said. Lawmakers like Rep. Grace Meng (D-N.Y.) and Rep. Adriano Espaillat (D-N.Y.) have also written to the USDA to reconsider the hot foods provision in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It’s just counterintuitive to most consumers now, that hot prepared foods would not be something available to SNAP customers,” Vollinger said.

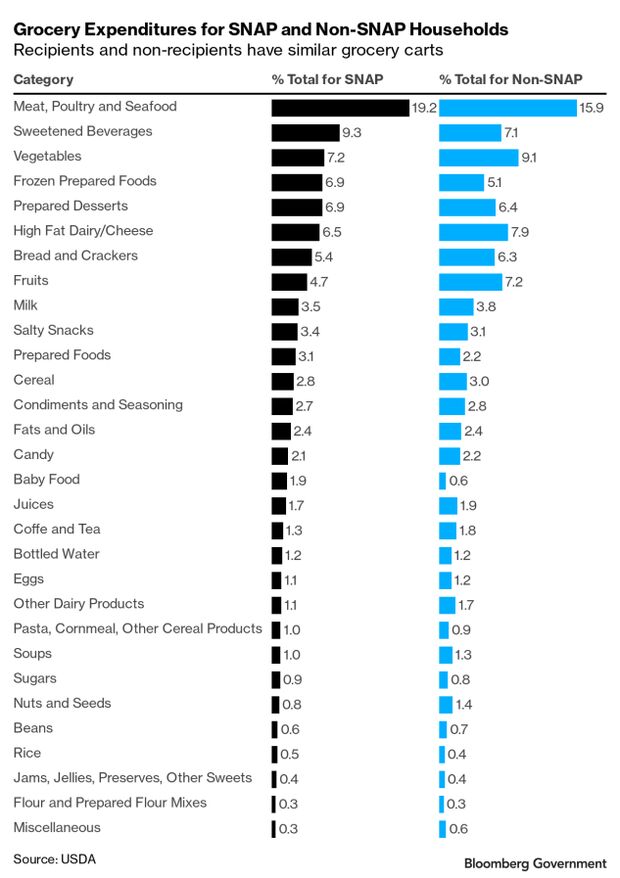

Households must meet multiple qualifications to receive benefits, but the general requirement is that they earn 130% of the poverty line or less. Lauren Bauer, an associate director at the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution, agreed that households that receive SNAP benefits shop by and large like every other American. Both groups spend the bulk of their grocery bills on staples like meat, poultry, and seafood, and a significant portion on vegetables. On the other hand, both groups spend a large chunk on sweetened beverages and desserts.

“When they are given extra resources,” she said of SNAP recipients, “they tend to buy more fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins.” For example, in a pilot program that gave SNAP recipients a rebate for healthy foods, they tended to consume more fruits and vegetables than before.

Bauer said areas for change in SNAP policy will likely be a focus of farm bill hearings, as well as the White House nutrition conference in September. But she thought Congress’s most important task with SNAP was to codify into law the ad hoc benefit increases for the program over the past couple recessions. In August, the USDA bumped up the average SNAP benefit by about 20% when it reevaluated the cost of a healthy diet.

Earlier: Expanding Food Aid Opens Fresh Partisan Divisions in Congress

But Bauer worries that making other changes to the program could backfire. “This is a very good program; it’s quite effective, not only because it’s efficient, but because it leverages incredibly important aspects of choice,” she said. “And if it’s not broke, don’t fix it.”

SNAP reduced household food insecurity in 2015 by about 17%, the Food Research & Action Center estimates, with the greatest impact on preventing hunger in children.

“Even though the rotisserie chicken issue is silly, and you should be able to provide it, if opening up that box calls into question the efficiency and effectiveness of the program, it’s probably not worth doing,” Bauer said.

Life Obstacles

Others, however, say the provision burdens households unnecessarily. Amy Jo Hutchinson, a food security activist in West Virginia, said she’s spoken to workers in her community who are frustrated that they can’t use their SNAP benefits during a lunch break to grab a prepared bite to eat.

“There are just so many life obstacles—like, how many times has your stove broken down? And either you couldn’t afford a repairman or just couldn’t do it?” said Hutchinson, a single parent who considers herself working poor. “You know, that’s just life whenever you’re poor.”

Almost 6% of the US population also lives in a “food desert,” or an area with low access to stocked grocery stores. With low-income Americans being more likely to live in a food desert, some SNAP recipients have easier access to convenience stores with prepared food than to grocery stores with raw ingredients.

Read more: U.S. Food Programs Said to Worsen Nutrition Woes for Poor (1)

The rule that prohibits prepared food purchases is waived in times of disaster to account for the loss of electricity and the means required to prepare food. The Restaurant Meals Program, too, is a state option that allows people to use their benefits at restaurants if they have a need like homelessness or disability.

“But it’s very underutilized,” Robert Campbell, senior director of policy at Feeding America, said, adding that the group is looking at ways to strengthen it. Only seven states—Arizona, California, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Rhode Island, and Virginia —operate Restaurant Meals program.

With food inflation hitting 9% above last year’s prices in April, food insecurity is especially in focus because low-income consumers feel the greatest hit to their pocketbooks. Items like rotisserie chickens that are low-cost and nutritious, advocates argue, are more important than ever as prices soar in the grocery store.

“The way the system works for people in the system is a lot different most times, quite often, from the way it looks on paper,” Hutchinson said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Maeve Sheehey in Washington at msheehey@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.