Regeneron, Janssen Drugs Fit Profile Targeted in Spending Bill

By Alex Ruoff, Jasmine Ye Han and Valerie Bauman

- Plan would negotiate prices of expensive older pharmaceuticals

- Moderate Democrats sought compromise to preserve innovation

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Democrats are advancing a plan to negotiate the prices of drugs Medicare spends the most on, potentially saving billions of dollars annually.

Medicine from Merck & Co., Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca PLC, and other major drugmakers could be targeted.

Democrats reached a compromise on their drug proposal that would allow the government to negotiate prices of medicines at least nine years out from their initial approval date. That means new drugs, which can make headlines with high sticker prices, wouldn’t be affected.

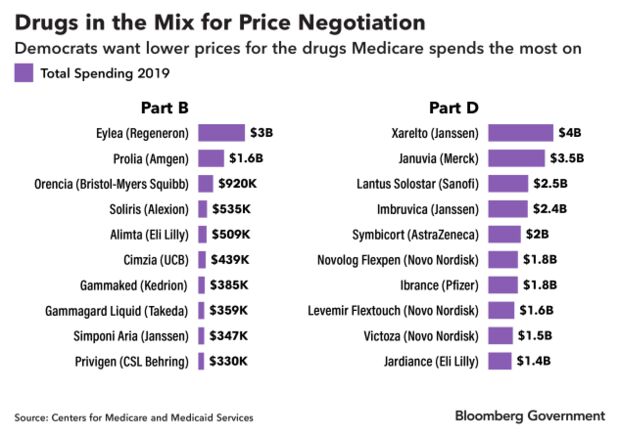

Nearly half of the prescription pharmaceuticals that were the top 10 costliest to Medicare’s outpatient drug and pharmacy benefits in 2019 could face negotiation, according to a Bloomberg Government analysis. Medicine administered in a doctor’s office is paid for under Part B of Medicare, and drugs obtained through a pharmacy are paid for under Part D.

The plan is part of Democrats’ sweeping social spending and tax package (H.R. 5376), which House leaders plan to vote on before Thanksgiving. It could still face changes before it becomes law.

“We’re coming out of the gate negotiating over the most expensive drugs: we’re talking cancer, arthritis, anticoagulants,” Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) told reporters last week. “That’s a significant change.”

The White House estimates the proposal would reduce government spending by about $100 billion over 10 years.

Medicare’s Costliest Drugs

Bloomberg Government identified 20 drugs in the latest Medicare data that would most likely be affected, though no formal selection has been made. The proposal wouldn’t take effect until 2025, so the makeup of drugs eligible for negotiation could change.

The head of the Department of Health and Human Services would pick 10 drugs out of the 100 costliest drugs for price talks with the manufacturers under the current proposal. Drugs approved in the last nine years, or 13 years for complex biologic drugs, would be excluded. The legislation would exempt orphan drugs, which treat rare diseases with narrow indications.

The list includes the macular degeneration drug Eylea, made by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., which despite being 10 years old costs Medicare $10,851 per beneficiary.

It also includes Xarelto, made by Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen Pharmaceuticals, one of the most-popular drugs for preventing blood clots. Medicare spent more than $4 billion on the drug in 2019, or $3,595 per beneficiary.

Many of the drugs that cost Medicare $1 billion or more in 2019 are at least a decade old and have a single manufacturer, meaning they have no cheap generic alternative. The proposal is aimed at bringing the prices of those drugs down. Merck’s diabetes drug Januvia has been on the market since 2006 and remains on the market exclusively. However, multiple generic drugmakers are challenging a patent that won’t expire until 2027, which could make a cheaper version available as soon as 2025, the year drug price negotiation starts under the bill.

John Cummins, a representative for Merck, said Januvia is expected to lose its exclusivity by 2025 and have multiple competitors by that time.

Lower Consumer Prices

Employer-sponsored health insurance and other private insurance wouldn’t be able to access the lower prices under the bill, despite some Democrats’ attempts to broaden the proposal. In theory, the government’s new authority under Medicare would bring prices down for everyone, although employer groups worry they’ll be charged even more for their employees’ prescriptions.

It will take time before seniors or other consumers see the benefit of this compromise policy, Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, said.

“If Democrats are able to enact this deal, they will be able to campaign on an issue very popular with the public, but Americans should not expect to see big discounts immediately when they go to the pharmacy,” Levitt said. “Savings will take time to materialize, and some people will see bigger benefits than others.”

Beyond negotiated prices, seniors on Medicare would have their drug costs capped at $2,000 per year and could “smooth” those costs evenly through the year starting in 2024 under the proposal. Currently, seniors pay a share of their drug costs while on Medicare, and the program provides catastrophic coverage for out-of-pocket costs greater than $6,550, as of 2021

The bill would also require drugmakers to provide rebates to the government for increasing the price of their drugs above inflation starting in 2023.

Innovative Drugs

The Democrats’ proposal would cut more deeply into the value of small molecule drugs—which historically have been more common medicines—than biologics, which are more complex and are often administered by physicians, Peter Kolchinsky, founder and Managing Partner at RA Capital Management LP, which invests in biotech companies, said.

Small molecule drugs would have fewer years of protection under the proposal, and they already tend to be less profitable than biologic drugs if a generic version reaches the market. Biologics often cost more, are harder to manufacturer, and their prices haven’t dropped as much when generic versions, known as biosimliars are developed, Kolchinsky said.

“They’re going in the wrong direction in terms of making novel drugs cheaper,” Kolchinsky said.

Rep. Scott Peters (D-Calif.), who opposed broader negotiation efforts, said preserving a drugmaker’s exclusivity period—where a company has the sole right to manufacture and sell a medicine—is crucial to ensuring companies continue to invest in new, innovative medicines. He joined three other House Democrats and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.) to keep negotiations focused on older medicines.

By allowing broad price negotiation on drugs new to the market, “you destroy the incentive drugmakers have to take risks on products that most of time don’t pay off,” Peters said.

Stephen J. Ubl, president and CEO of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the main lobbying organization for large drugmakers, called the proposal “disastrous” in a statement. He said it would “upend the same innovative ecosystem that brought us lifesaving vaccines and therapies to combat Covid-19.”

Longtime supporters of allowing Medicare to negotiate prices said they’d prefer a broader authority.

“It’s a long way from where I hoped we would be, but it’s a long way from where we were,” Rep. Peter Welch (D-Vt.) said.

Not a ‘Nothing Burger’

Benedic Ippolito, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute said the new policy could alter the calculations investors make about the value of some products. He disagreed, however, that the change would widely stifle investment in new medicines.

“It’s not a complete nothing burger,” he said. The most recent version of the drug pricing proposal is “less impactful” than an earlier bill (H.R. 3) that would have allowed negotiation on as many as 250 drugs with no restrictions related to how long they’ve been on the market. The earlier bill wouldn’t have passed in a 50-50 Senate.

Drugmakers typically assume they’ll maintain a monopoly on a new drug for about a decade and longer for complex biologics, Ippolito said. The drug pricing proposal would largely cut into profits toward the end of that monopoly, not during the crucial early years.

The idea that drugmakers get a government-backed monopoly for a period of time to recoup their investment in new drugs and then must face competition has long been the “social bargain” of the U.S. pharmaceutical approval system, Rachel Sachs, a professor at Washington University School of Law who studies health policy, said.

Adding government negotiation to ensure prices go down after nine or 13 years effectively reinforces that bargain, she said.

“This gives us a backup system,” she said.

An Answer to Patent Extensions

While small molecule drugs would be subject to negotiations earlier, many of the costliest drugs to Medicare are biologics. Of the 20 drugs identified by Bloomberg Government as likely candidates for price negotiation, more than half are biologics.

The market exclusivity for biologics is often extended by minor adaptations. For example, Novo Nordisk A/S‘s Novolog Flexpen is an insulin drug with a newer patent on its injection device. The drug pricing proposal, pegged to the first year of a medicine’s approval, would make the Novolog Flexpen eligible for government price negotiation.

Natalia Salomao with Novo Nordisk, said her company provides “steep discounts” to federal programs that keep Medicare premiums from rising greatly.

“Government intervention in Medicare pricing is an extreme policy that would not address costs seniors face and would serve to disrupt access to medicines available for seniors,” she wrote in an email.

Other drugs that made Bloomberg Government’s list had their market exclusivity extended via new patents, such as Imbruvica, a small-molecule cancer drug made by Janssen, which was first approved in 2013, but has 40 patents protecting it until at least 2031.

Similarly, AstraZeneca’s asthma drug Symbicort was first approved in 2006. With 10 patents, its exclusivity is protected until mid-2023.

Representatives for AstraZeneca and Janssen didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Alexandra Bowie, a spokeswoman for Regeneron, said it was “too soon to speculate” on the impact of the proposal.

Representatives for Amgen Inc. and Eli Lilly & Co. declined to comment for this story. Representatives for AstraZeneca, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., and Pfizer Inc. didn’t respond to a request for comment. Sanofi, UCB SA, CSL Behring LLC, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., and Kendrion NV also couldn’t be reached for comment.

To contact the reporters on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com; Jasmine Ye Han in Washington at yhan@bloomberglaw.com; Valerie Bauman in Washington at vbauman@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John Dunbar at jdunbar@bloomberglaw.com; Sarah Babbage at sbabbage@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.