Liver Transplant Tug-of-War Pits NYC, Chicago Against Rural U.S.

By Alex Ruoff

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

- Shorter organ wait times in prospect for patients in cities

- Don’t punish some states’ innovations, rural senators say

Senators from states where patients have long enjoyed some of the easiest access to transplanted livers are balking at coming changes to how donated organs are distributed.

People with failing livers in states including Florida, Kentucky, Iowa, and South Carolina typically get organ donations earlier than patients in California, Maryland, and New York, according to federal data. The national system for determining who gets donated livers, however, is set to change this year to benefit those areas where people with liver disease have historically faced longer waits, such as Chicago and New York City.

A group of 22 rural-state senators recently pushed back against the changes, asking the head of the Department of Health and Human Services to look into whether new rules would punish some states that worked to reduce the wait time for organ donations.

“Specifically, this policy change does not appear to give any weight to locations that have been successful in reducing their wait lists through aggressive organ procurement or through adopting innovative transplant techniques,” the lawmakers said in a Jan. 22 letter.

The letter was sent by several influential lawmakers including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Sens. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), who heads the panel responsible for funding the HHS, and Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee.

The lawmakers are awaiting a response to their letter before taking more action but their opposition could complicate the rollout of the changes, starting at the end of January, congressional aides said.

They’ve got motivation to stay on top of the issue: Hospitals and clinics that specialize in organ transplantation are warning they could close down under the changes.

Changes to Come

The changes are meant to fix the long-time geographic disparity in the availability of livers nationwide.

There is a nationwide dearth of organs: 20 people on average die each day waiting for transplants, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, the nonprofit that oversees organ donation and transplanting in the U.S.

When a liver becomes available it is offered first to people who are registered in transplant centers associated nearby, but can be distributed to another region of the country if no local match is found.

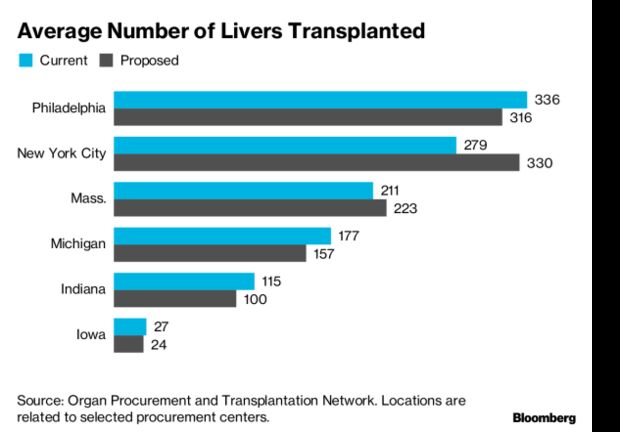

Starting this year, livers will first be made available to people who are located within a 500-mile radius of the donor hospital favoring those considered the sickest and more in-need of an organ. This move is slated to make more than 50 livers available in New York City every year, but will lower that number in rural areas.

Having fewer organs available means fewer transplant surgeries, endangering the growth and development of hospitals in rural areas, Alan Reed, director of the University of Iowa Organ Transplant Center in Iowa City, said. These centers need to perform enough transplants to remain in good standing with insurers and accreditation organizations, he said.

The Health Resources and Services Administration, which oversees the organ-sharing network, estimates Iowa will see as many as five fewer liver transplants per year under the changes, which represents between 20 percent and 16 percent of all the transplants done at the University of Iowa. These transplants are expensive and often publicly funded: it costs between $40,000 to $60,000 just to procure a liver and many people who receive the procedure are covered under Medicaid, Reed said.

“If HRSA’s goal is to close programs than this will succeed,” Reed said.

The organ-sharing network argues the changes will mean fewer people, particularly children, will die waiting for an organ.

“The Board carefully weighed a number of options, with the ultimate goals of best honoring the gift of organ donation and helping those in greatest need,” Sue Dunn, President, UNOS Board of Directors, said in a statement.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.