Even Hawks See Room for Deficits—if Congress Could Curb Itself

By Jack Fitzpatrick

- Biden budget plan could come as early as next week

- Some Republicans no longer flinch at trillion-dollar deficit

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

While the pending White House plan to fund the federal government will elicit the usual GOP handwringing on Capitol Hill, even Republican budget experts say they’re OK with deficits that may shock everyday Americans.

The government could theoretically run annual deficits—the difference between government spending and revenue—in the hundreds of billions of dollars without any problems, conservative lawmakers and experts increasingly acknowledge. What they really want is rules that would require Congress to keep deficits in check, compared to economic growth.

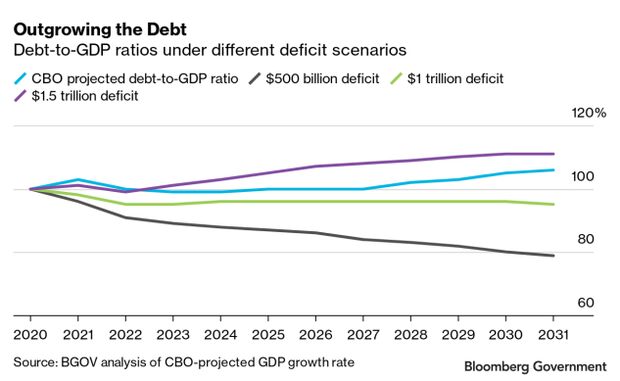

“You’re in the 500 billion to a trillion dollar” annual deficit range to responsibly reduce the national debt as a percentage of gross domestic product, said Marc Goldwein, senior vice president and senior policy director for the fiscally conservative Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. “You can have what we used to consider some pretty large borrowing and still have debt on a downward path as a share of GDP.”

And Bill Hoagland, a senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former Republican staff director for the Senate Budget Committee, said flatly: “I’ve given up on a balanced budget ever again.”

President Joe Biden’s budget proposal, expected as soon as next week, will likely call for annual deficits surpassing $1 trillion. Biden promised in his State of the Union address Tuesday night that this year’s deficit will be “less than half of what it was before I took office.” The fiscal 2020 deficit was $3.1 trillion.

Imposing Discipline in Congress

Budget hawks don’t like those figures, but a more conservative deficit may not be too far off. A plan to stabilize or reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio could involve deficits larger than the U.S. defense budget.

“If you keep it below a trillion dollars, you’re reducing the deficit each year relative to GDP, because we’re keeping up economic growth and inflation,” Goldwein said. “That’s not the level the CRFB is advocating, but if you could consistently keep deficits below a trillion dollars forever, you would ultimately be on a decent path.”

That logic contrasts with rhetoric from Republican—and some Democratic—elected officials advocating for a balanced budget.

Sen. Mike Braun (R-Ind.) forced a Senate floor vote in February on a measure to require the federal government to balance its budget, and 47 senators supported it, including Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin (W.Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (Ariz.). A House measure to amend the Constitution to require a balanced budget has 46 Republican cosponsors.

Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.), chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, put forward a governing plan calling on officials to “sell off all non-essential government assets, buildings, and land” to pay down the debt. Members of the Republican Study Committee have regularly offered budget outlines touting their plans to balance the budget.

But even some supporters of a balanced budget requirement say it’s possible to responsibly run a deficit. The challenge, they say, is to create rules that would impose discipline in Congress so those deficits remain responsible.

“Theoretically, if you were disciplined, and you keep growing the economy and have deficits stay the same—shrinking by definition each year—you can run deficits,” Braun said in a March 2 phone interview, referring to the expectation that a steady deficit would shrink in comparison to a growing economy. “And it’d be better, of course, than what we’re doing now, which is they’re getting larger as a percentage of GDP.”

Lack of Spending Rules

Congress has few, if any, fiscal rules that it consistently follows.

“We don’t budget, so there’s no chance of, ‘Do we need more of this or less of that?’—it’s only how much more,” Braun said.

The GOP believes “tools like spending caps or debt-to-GDP targets can absolutely help curb the explosion in government spending,” Rep. Jason Smith (R-Mo.), the top Republican on the House Budget Committee, said in a statement.

Doug Holtz-Eakin, president of the conservative think tank American Action Forum and a former Congressional Budget Office director, said he likes the idea of a balanced budget amendment because Congress needs rules put in place to force fiscal accountability. But he agreed that the federal government can run a deficit and that lawmakers should focus on gradually reducing the debt as a percentage of GDP.

“There isn’t a magic number, as long as it’s stabilized and headed south,” Holtz-Eakin said in a recent phone interview.

Economic growth is projected to waver between 3.3% and 3.8% annually between 2023 and 2031—after sky-high nominal rates of growth in 2020 and 2021—according to the CBO, meaning deficits totaling 3% of GDP would consistently reduce the debt-to-GDP. According to those GDP estimates, a deficit of 3% of GDP would total $767 billion in 2023 and $982 billion in 2031.

Hoagland from the Bipartisan Policy Center said he’d like to see the debt-to-GDP ratio drop “into the 90% range” by 2031. Longer-term, a ratio between 60% and 90% “would be a major achievement,” said Hoagland.

To meet Hoagland’s 90% goal, the publicly held debt could rise to $30.3 trillion in 2031, from $23.2 trillion in fiscal 2021, according to the CBO’s GDP projections. The office has projected that the debt will rise to 106% of GDP, or $35.8 trillion, in 2031.

‘Don’t Really Have a Number’

Imposing rules to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio is the fiscally conservative position. But liberal lawmakers and economists say there’s no reason to think the federal government can’t continue to increase the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Fiscal hawks warned that the debt shouldn’t surpass 60% of GDP, and today’s warnings about the 100% level seem equally arbitrary to liberals.

“Everybody says, ‘Oh, we’re at 100% of GDP.’ Well, does that mean anything?” Rep. John Yarmuth (D-Ky.), chair of the House Budget Committee, said in a phone interview.

Yarmuth served on a joint select committee in 2018 tasked with reviewing the budget process. Members discussed a more formal target debt-to-GDP ratio, among other changes, but failed to approve any proposal. The process convinced Yarmuth that rule changes can’t save Congress from itself, he said.

Lawmakers should focus more on what they’re spending money on, rather than metrics such as the debt-to-GDP ratio, Yarmuth said. Spending on measures that increase economic capacity can have an anti-inflationary effect and are often more justifiable than funds to boost demand, he said. For example, federal funds for housing vouchers would be nonproductive and inflationary if there’s not enough housing stock to meet the increased demand, Yarmuth said.

If forced to pick a healthy level for the federal deficit, Yarmuth said he’d recommend 3% to 4% of GDP. But that’s beside the point, he said: “You really have to think about how you’re spending it, how the deficit is constructed.”

Yarmuth said he favors a November 2020 proposal by former Council of Economic Advisers Chair Jason Furman and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers that policymakers should focus less on the debt-to-GDP ratio and more on keeping the government’s real interest payments below 2% of GDP each year.

Liberal economists agree that different kinds of spending should be treated differently and that lawmakers shouldn’t view deficit metrics as their only goal.

“Economists don’t really have a number,” Louise Sheiner, policy director for the Brookings Institution’s Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, said in a phone interview. “We don’t know how high the debt can go in the long run.”

The debt-to-GDP ratio is a useful tool for tracking the effective size of the federal debt, but it shouldn’t be used as a policy prescription, Paul Van de Water, senior fellow at the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said in an interview.

“We can agree what thermometer we should use, even if you like the room hotter than I do,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jack Fitzpatrick in Washington at jfitzpatrick@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com; Brandon Lee at blee@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.