Deadly Tumors, Surgical Lapses: Troops Court Trump in Bid to Sue

By Roxana Tiron and Travis J. Tritten

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

- Green Beret with cancer met with Trump and Pence for support

- Congress mulling bill to permit medical malpractice suits

Congress is closer than ever to toppling a seven-decade-old legal ban on U.S. troops suing over military medical malpractice, and advocates see President Donald Trump‘s recent encounter with a terminally ill Green Beret as possibly giving the campaign a decisive push.

Trump’s support could sway the Republican-controlled Senate to support a provision in the House Democratic majority’s version of the annual defense policy bill that would create an exemption to the Federal Tort Claims Act, allowing troops to file malpractice suits in federal court. Because the Pentagon opposes the change, White House support could be crucial as the House and Senate negotiate a final authorization bill.

Advocates became optimistic about Trump getting engaged after direct appeal this month by a soldier battling advanced lung cancer that he says military doctors missed.

“It’s never too late, don’t give up,” Trump told Army Sgt. 1st Class Richard Stayskal, shaking his head after hearing the Green Beret’s story when they met at a North Carolina rally.

The so-called Feres doctrine evolved from a 1950 Supreme Court decision barring lawsuits when active-duty troops are injured or killed due to medical mistakes in military hospitals. Victims have attacked the policy in court for years. But the Supreme Court declined to revisit the matter in May despite a sympathetic dissent from Justice Clarence Thomas, shifting the focus to Congress and the president.

While the measure to end the Feres doctrine is in a Democratic proposal, the House stand-alone bill (H.R. 2422) that ended up inspiring the provision was co-sponsored by Rep. Markwayne Mullin (R-Okla.), who has become close to Stayskal.

Other backers of the Sergeant First Class Richard Stayskal Military Medical Accountability Act of 2019 include Reps. Richard Hudson (R-N.C.), whose district includes Fort Bragg, where Stayskal is stationed; Guy Reschenthaler (R-Pa.); and Greg Steube (R-Fla.), as well as Democrats Jamie Raskin(Md.), Ted Lieu (Calif.), and Charlie Crist (Fla.).

Stayskal’s home-state senator, Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), chairman of the Senate Armed Services Personnel Subcommittee, said he wants to proceed carefully because of the impact of upending Feres. But he and some other Republicans said they see merits to altering the ban as it now exists.

“I do believe there are points in time where you have a very sympathetic case and you would like to create some balance,” said Tillis, who talked with Stayskal at the rally. Stayskal also met with Tillis and Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.), a member of the Judiciary Committee, on July 25. Kennedy, who’s a supporter of the change, had introduced an amendment to the Senate’s version of the defense authorization bill (S.1790), but it was not considered.

Pentagon Rebuke

The Pentagon said it hasn’t estimated the costs of allowing claims by active-duty troops, but lawmakers say it will be about $440 million over a decade.

Military spouses, family members, and retirees are already permitted to sue and the Pentagon said it paid out 67 malpractice claims for a total of $59 million in fiscal year 2018.

“It’s not going to cost that much money. If we get competent medical providers, I guess it wouldn’t be a problem,” said Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Calif), an Armed Services subcommittee chairwoman and lead sponsor of the bill.

The Pentagon, in a rare public rebuke of pending legislation, opposed the Feres legislation. It maintains the system of medical accountability and its existing compensation benefits to troops who are injured or killed in such incidents is adequate.

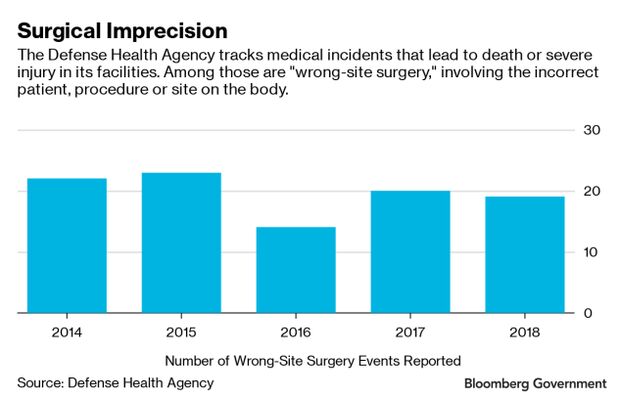

Military practitioners report the incidents to the Defense Health Agency including how they occurred and corrective actions, though the Government Accountability Office found last year that the process is fragmented and the agency might not get complete information. Outside peer review is also used to weigh medical incidents and doctors report to the National Practictioner Databank, a clearinghouse created by Congress to track the performance of providers, Lisa Lawrence, a spokeswoman, said in a statement.

Meanwhile, troops are covered by a $400,000 life insurance policy, unless they opt for a lower coverage amount, and have access to disability pay and benefits. Families of troops are entitled to annuity payments and a variety of death benefits when service members are killed.

The military has seen no evidence that allowing the lawsuits will improve care, Lawrence said.

“Rather, more malpractice suits would likely bring defensive medicine practices into military health care, compromising everyday medical decision making essential to military readiness,” Lawrence said in a statement.

Medical Incidents

The Pentagon tracks medical incidents that lead to death or severe injury in the military’s global system of hospitals and clinics. Those increased to 319 in 2016 from 121 in 2013 , according to a Government Accountability Office report last year.

The increase could be partly due to new reporting policies, GAO found, and the events do not necessarily involve medical malpractice.

The figures appear higher than what is typical in civilian medical care because the military uniquely includes dental incidents in its internal tracking, Kevin Dwyer, a spokesman for the Defense Health Agency, said in a statement.

The Pentagon “holds itself to a higher standard of event reporting than civilian counterparts and internally reports on a broader range of events for improvement,” Dwyer said.

Critics say the quality of military medical care is substandard compared with civilian hospitals. There’s a lack of accountability because the Feres doctrine has shielded providers from lawsuits, said Dwight Stirling, chief executive officer for the Center for Law and Military Policy think tank in California.

“There is a mentality of being beyond the reach of their patients. They think to themselves, ‘What can my patient do if I make a mistake?’” said Stirling, an Army major in the California National Guard’s judge advocate general corps who recently completed a doctoral dissertation on the Feres doctrine.

Malpractice Insurance

Because troops can’t sue over their treatment at military facilities, doctors there often don’t have malpractice insurance as most civilian hospitals, clinics, and medical facilities require, said Natalie Khawam, with the Whistleblower Law Firm, who’s taken on Stayskal’s case.

“When a physician commits malpractice, he or she is dropped by their insurance carrier.” Khawam said in an e-mail. “Only DoD medical facilities and VA

hospitals do not require their civilian physicians to carry malpractice coverage. Given the fact that they are uninsured, the soldiers are not only receiving substandard care, they are unable to have legal recourse.”

If the Defense Department is willing to take on civilian doctors without malpractice insurance, it “has to be responsible for them,” Mullin said. Either the doctors need to be required to carry insurance, or “they need to be held responsible when they do have malpractice cases,” he said.

Deadly Tumor

Stayskal went to Womack Army Medical Center at Fort Bragg in 2017 after feeling suffocated and coughing up blood, but the hospital misdiagnosed him with pneumonia during two visits, according to his congressional testimony before the House Armed Services Committee.

By the time he saw a civilian doctor six months later, the lung tumor causing the problems had doubled in size. The tumor had showed up in X-rays done before he went to dive training, but nobody told Stayskal or diagnosed him.

“Rich is still with us, but he’s terminal — 100 percent could have been avoided,” Mullin said.

Rebecca Lipe, an Air Force veteran, said military providers first claimed an extramarital affair and sexually transmitted disease were to blame when ill-fitting body armor in Iraq damaged her reproductive organs. Over more than a year, the military performed two unnecessary surgeries, treated her for malaria, and prescribed hormones that damaged her body and relationship with her husband.

A military hospital then lost the remains of her baby after a miscarriage and failed to do gender and genetic testing, which could have helped the chances of future pregnancies, said Lipe, who was able to give birth after leaving the military and receiving civilian treatment.

“I have a daughter that one day both my husband and I would love for her to look at going to a service academy and serving her country,” she said in an interview. “But I also want to know that she’s going to join a military that is going to protect her when she raises her hand and if something happens she has a remedy for that situation.”

The case of Rebekah Daniel, a Navy lieutenant who bled to death during childbirth in 2014 at Naval Hospital Bremerton in Washington state, was stopped short of reaching the Supreme Court in May. Her surviving husband sought to challenge the Feres doctrine but the high court denied his petition with a dissenting opinion by Thomas, who lamented the “unfortunate repercussions” of the doctrine.

“They particularly are hesitant of overruling precedent when the Congress could fix the issue,” said Andrew Hoyal, of the Luvera Law Firm, who represented husband Walter Daniel.

The Senate’s Turn

As negotiations are set to start on the defense authorization bill, some key Republican senators have yet to study and weigh the consequences of the House provision.

“This is not something that came up in our committee,” Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Jim Inhofe (R-Okla.) said in a short interview.

Mullin, who’s close to Inhofe, said that he and Stayskal have met and discussed the issue with the senator’s office. “Sen. Inhofe’s office is from all indications, I can’t speak for them, but from all indication, is fine with it,” Mullin said in an interview. “We’ve been working close with them. We are not trying to change the whole Feres Doctrine; we are trying to cover our men and women in uniform.”

Stayskal and other advocates say they are optimistic that the White House could encourage senators to get on board, though it has not yet voiced any official support.

“I think any good word enforcement from Trump is really going to help keep it in” the defense bill, said Kate Ilahi, director of government affairs for the American Association for Justice, which represents trial lawyers.

Stayskal has taken his case in person not only to senators and to Trump, but also Vice President Mike Pence—twice. Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s lawyer, has been involved as well: he made a personal phone call to the president to make him aware of Stayskal’s situation before they met at the North Carolina rally, Stayskal recalled in a telephone interview.

He’s hoping the influence campaign will be enough.

“I don’t want to count on anything too early,” Stayskal said. “We’ve got a really good shot.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Roxana Tiron in Washington at rtiron@bgov.com; Travis J. Tritten at ttritten@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.