Black Communities Face Wider Food Shortfalls as Covid Saps Jobs

By Megan U. Boyanton

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Democratic lawmakers and anti-hunger advocates are calling on the Agriculture Department to broaden food assistance to mitigate a longstanding inequity Black Americans face that’s now aggravated by the coronavirus pandemic.

“Food insecurity has been impacting African-Americans disproportionately for decades,” said Minerva Delgado, director of coalitions and advocacy at the Alliance to End Hunger. “That racial gap has been there all along.”

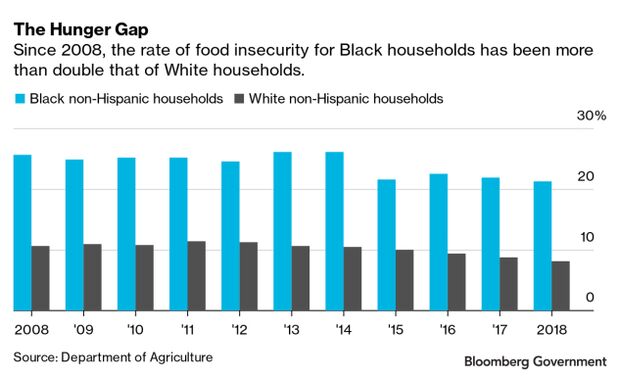

Black households already experienced the highest racial rate of food insecurity before the pandemic hit: 21.2%—more than double the 8.1% among White households, the Agriculture Department says. The situation has since worsened: 45% of Black adults said they’ve skipped meals, or relied on charity or federal food assistance since February, compared with 18% of White adults, the Kaiser Family Foundation, a health policy nonprofit, found.

Racial injustice and disparities have been on display since George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, died in Minneapolis police custody May 25, triggering weeks of protests nationwide. Cities and states are also navigating how to reopen businesses after leaders directed residents to stay home for months to slow the spread of Covid-19. The workplace shutdowns caused 21 million Americans to claim unemployment as of May.

Food banks are struggling to keep up with demand as one-fourth of the public is gripped by hunger, the Kaiser Family Foundation reports. At the same time, states are moving to expand a pilot program that lets food aid recipients shop online at authorized retailers, including Walmart Inc. and Amazon.com Inc.

Congressional Democrats pointed to the plight of low-income and communities of color living in food deserts in a June 9 letter to Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue. Some 23.5 million Americans live in areas lacking easy access to healthy, affordable food, with grocery stores farther than one mile away. Senate Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Committee ranking member Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) was among the 22 senators urging Perdue to focus on working to reduce food deserts.

One answer could be expanding the pilot program that lets Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program recipients order their groceries online with delivery options, advocates say. The pilot included in the 2014 farm law (Public Law 113-79) was launched in New York in April 2019, and has grown swiftly since January: The program operates in Washington, D.C., and 36 states, with four additional states approved, but still planning their roll-outs.

“COVID-19 has magnified the significant food insecurity facing communities of color across our nation, but it is important that we acknowledge that the need for increased SNAP benefits and access to nutritious, affordable food existed long before COVID-19,” said Rep. A. Donald McEachin (D-Va.), the Congressional Black Caucus whip.

In total, more than 90% of SNAP households will be covered by online purchasing, the department reports. Retailers determine the availability of home delivery, and federal benefits don’t cover the related fees.

The approval of online purchasing in SNAP isn’t limited to a certain time frame or number of states, a department spokesperson said in a June 12 statement. Ultimately, the responsibility is on state agencies, their third-party processors, and any retailers who wish to participate, the official added.

Looking Forward

Delgado at the Alliance to End Hunger said different factors, such as low-wage work and lack of affordable housing, compounded by “the racial wealth gap,” contribute to food insecurity.

“Food deserts continue to be a challenge,” she said. “However, the expansion of online purchasing using SNAP benefits is helping to address this problem.”

The program’s power lies in its ability to “work at scale,” Delgado said. While data on the number of SNAP recipients without internet access wasn’t readily available, those users would “be assisted by additional purchasing power in their usual method of accessing food,” she added.

The strength of federal food programs will remain critical for hungry Americans post-pandemic, said Geraldine Henchy, director of nutrition policy at the Food Research & Action Center, an anti-hunger nonprofit.

With the U.S. economy hurtling into a recession, Henchy said, recipients seeking government assistance—often the “first fired, last hired” employees—will be hit harder in the future, as President Donald Trump‘s administration pushes to tighten work requirements.

To tide over households reliant on monthly aid, SNAP’s maximum benefit should increase by 15%—a provision included in the HEROES Act (H.R. 6800), a virus-relief bill that stalled after the House passed it in May—Henchy said.

“Make SNAP a program that people can keep using, that they’re not going to get thrown off of,” Henchy said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Megan U. Boyanton in Washington at mboyanton@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.