Biden’s Climate Promises Challenged by Highway Money Influx (1)

By Lillianna Byington

- Republicans concerned about guidance against road expansion

- Roundabouts, low-carbon construction priorities in some states

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The Biden administration wants federal infrastructure money used to fix crumbling roads and bridges before being spent to build new ones, in part to limit climate change. Even so, the White House may have little say in how hundreds of billions of dollars are deployed.

Republicans are bashing as federal overreach administration directives on how to spread the infrastructure funds, and the back-and-forth has become contentious in recent weeks as money from the new law starts to flow to states.

“The administration put out guidance saying, ‘We’d really like you to take care of what you built before you build new things,’” Beth Osborne, director of the advocacy group Transportation for America, said referring to the recent guidance. “And they said: ‘Maybe so, but make me.’”

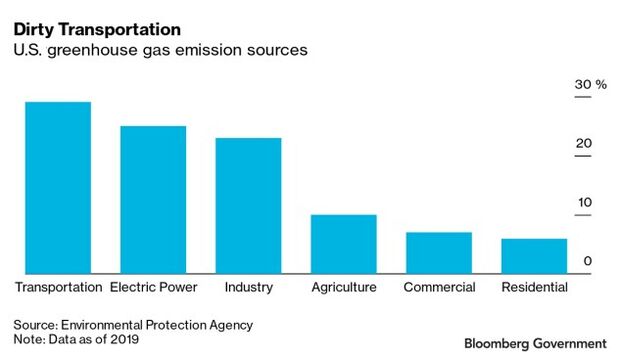

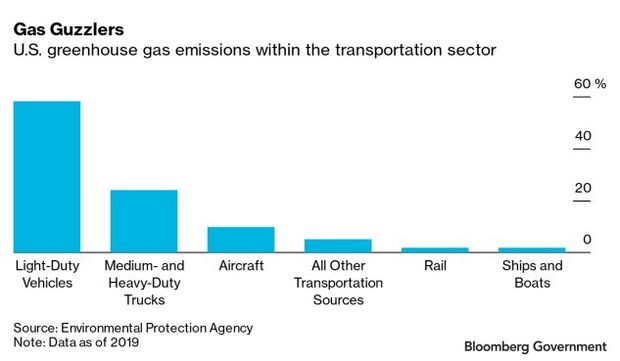

Over the next five years, the $1 trillion infrastructure package (Public Law 117-58) that Congress enacted in November will send hundreds of billions of dollars for roads to states, where expansion projects and highway building have contributed to the transportation sector generating the largest share of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions.

States are getting $52.5 billion this fiscal year for federal-aid highway formula funding, a 20% boost, according to the administration’s infrastructure guidebook out last week.

Some Democrats want tighter emission limits on road spending, and a focus on projects that decrease fossil fuel consumption. Republicans generally favor a federal hands-off approach to how states and localities spend the funds.

“Our largest single investment was in highways,” said Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), part of the bipartisan group that negotiated the infrastructure bill for months. “You can imagine our surprise when we see the Department of Transportation indicating that the highway money can’t be used for increasing capacity of highways. This direction flies in the face of our intent and our needs.”

Despite letters from Republican-led states complaining about the instructions, the guidance isn’t binding. Governors have the power to dole out formula funds—the larger pot of money—where they want.

Still, the Transportation Department retains control over other discretionary money in the bill, including billions of dollars in grants, signaling years of political wrangling ahead over what the White House declared a “once-in-a-generation investment in our nation’s infrastructure and competitiveness.”

Resistance and Road Expansion

In “most cases” highway money through the infrastructure law should be used to repair and maintain existing infrastructure before spending on “expansions for additional general purpose capacity,” Federal Highway Administration Deputy Administrator Stephanie Pollack said in the guidance memo dated Dec. 16.

That direction was “bolder than what I’ve seen before,” said Osborne. The White House reiterated its position last month when Infrastructure Implementation Coordinator Mitch Landrieu wrote governors, stressing that the $52.5 billion apportioned to states this year be used “to repair” roads and bridges.

The language raised some red flags.

“Excessive consideration of equity, union memberships, or climate as lenses to view suitable projects would be counterproductive,” 16 governors said in a letter to President Joe Biden. “A clear example of federal overreach would be an attempt by the Federal Highway Administration to limit state widening projects,” they said, adding that it would penalize rural states and those with growing populations.

“Send us the money. Give us flexibility,” Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, said at the White House last week. “We will spend it and you can audit us.”

Rep. Sam Graves (R-Mo.), ranking member on the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, said the Transportation Department “may not be following congressional intent,” and asked Landrieu to brief the panel. A White House spokesperson didn’t respond to requests for comment.

While Tennessee operates under a “fix it first philosophy,” a spokesperson for Gov. Bill Lee (R), who signed the governors’ letter, said states need autonomy in how to spend the federal funds. Lee’s recently proposed budget includes road widening and repair projects.

Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.Va.), who helped write the infrastructure law, raised similar concerns in a letter to governors with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) Wednesday. The senators said the law doesn’t discourage specific projects like added highway capacity, adding that the FHWA memo “has no effect of law, and states should treat it as such.”

Although states hold the purse strings on their formula dollars, the Transportation Department is starting to roll out discretionary programs that will factor in climate change and equity for applicants. But many new provisions, such as the carbon reduction program authorized in the law, can’t move forward until lawmakers agree on a year-long appropriations bill.

Greener Ways

Some states are starting to explore greener projects that could further separate how transportation spending looks based on region of the country.

The Colorado Transportation Commission’s new rule requires state and local planning organizations to evaluate transportation projects’ possible effects on climate emissions.

The state is relying on modeling to help meet new targets. If a project falls short, the agency could recommend adding capacity for bus rapid transit into a highway project, said Shoshana Lew, executive director of Colorado’s Department of Transportation.

“It doesn’t do much good to have a policy that’s about models in the abstract if the day-to-day projects don’t actually comport with those values,” Lew said.

Michigan is building a road that will charge electric vehicles as they drive. Other areas are exploring low-carbon cement, roundabouts, and diverting highway funds to transit projects.

Jim Brainard, Republican mayor of Carmel, Ind., has overseen the construction of more than 100 roundabouts in his city, noting that they move 50% more cars per hour than a stoplight, save fuel, and cut carbon emissions. The congestion mitigation portions of federal highway law include incentives to build roundabouts, said Brainard, who called fighting climate change “a nonpartisan issue.”

The infrastructure law’s massive road and bridge spending will be a boon to the construction material market. Climate activist groups, such as the Natural Resources Defense Council, have said whether the spending hurts or helps climate goals will depend on the type of projects funded and the types of materials used.

Concrete Still a Barrier to Climate-Friendly Infrastructure Plan

Buying lower-carbon cements with infrastructure dollars would save energy and cut greenhouse gases emitted, said Sean O’Neill, senior vice president for government affairs at the Portland Cement Association, which represents cement manufacturers. Traditional concrete accounts for at least 7% of climate-change-fueling carbon dioxide emissions globally, according to BloombergNEF.

‘Extremely Hard’

Transportation has largely been built around facilitating the movement of vehicles in traditional ways, and most states have bought into that paradigm, said Norman Garrick, professor emeritus of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Connecticut. Changing the way states think about spending federal transportation money is “extremely hard,” he said.

In Georgia, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp raised concerns about not being able to deploy expansion projects, while its Democratic delegation asked the state’s Transportation Department for plans on how officials can flex Federal Highway Administration money to support public transit over the next five years.

A planned expansion of the I-20 and I-285 interchange east of Atlanta has raised environmental justice concerns, Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.), told the Georgia Department of Transportation and U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg in a Feb. 4 letter.

“A project that worsens pollution, fails to remove congestion, and makes it more difficult to build proposed transit expansion projects in the corridor seems like a particularly ineffective use of federal transportation funds,” he wrote.

Even states that prioritize repair can’t ignore the political boon that can accompany the unveiling of a new highway or bridge, said Osborne.

“Lots of times governors want to build new things because, I mean, frankly, you get a lot better press building new things than repairing,” she said.

“Just think about the press that comes with a major rehab of a bridge: Traffic will be backed up,” she noted. “But you build a brand new bridge, while not repairing things: Ribbon-cutting, great press. There’s a lot of political push to do what gets you credit.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Lillianna Byington in Washington at lbyington@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.