Banning ‘Junk Foods’ From Nutrition Aid Provokes Partisan Fight

By Maeve Sheehey

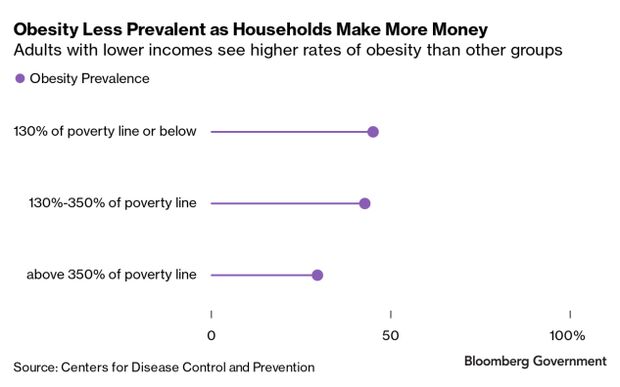

- Obesity rates higher among households with less money

- Lawmakers divided on offering restrictions versus incentives

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Restricting what federal food aid recipients can buy with their benefits has incensed Democrats and divided Republicans, stoking heated debates about government overreach, an ailing American population, and how welfare should work.

But as lawmakers look to address the increasingly poor health outcomes for low-income Americans, nutrition programs that offer healthy eating incentives instead of restrictions are garnering support on both sides of the aisle. Such approaches could make it into the five-year reauthorization of the farm bill, which expires after September — though they will have to contend with spending constraints on Capitol Hill.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the largest US nutrition aid source that reaches more than 40 million people a year, doles out monthly dollars to low-income individuals and families to spend on food. While SNAP recipients can’t use their benefits to buy hot foods or restaurant meals, most groceries are fair game.

Some hard-right Republicans have floated changing those food rules. They say restricting what SNAP recipients can buy would lead them to consume more vegetables and less junk food.

“Why should our taxpayer dollars be allowed to be spent on junk foods that provide no nutritional value and contribute to America’s obesity epidemic?” said Rep. Josh Brecheen (R-Okla.), who introduced a bill that would limit what SNAP recipients can buy with their benefits. The measure would exclude ice cream, soda, candy, and prepared desserts from the program.

The bill, whose Senate companion (S. 1485) is led by Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), has no Democratic cosponsors. Top Democrats involved in nutrition policy say SNAP food restrictions would increase bureaucracy and harm families without delivering positive results.

That isn’t stopping conservatives such as House Appropriations subcommittee leader Andy Harris (R-Md.) from using the annual appropriations legislation to roll out language authorizing pilot programs on SNAP food restriction.

“Today, much of our nutrition debate focuses on the health inequality of lower-income and minority Americans, while glossing over the root cause of the disparity — unhealthy government-funded food,” Harris wrote in a May essay for RealClearPolicy.

Rationale of Restrictions

Obesity rates are higher among households that earn lower wages, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s spurring the push to encourage healthy eating in federal nutrition programs such as SNAP, which are targeted toward low-income people.

SNAP recipients largely buy the same groceries as the average American, and the CDC estimates that only about a tenth of Americans eat at least the daily 1.5 cup serving of fruits, or two cups of vegetables that the US Department of Agriculture recommends.

Getting people to eat more vegetables is complicated. Fresh produce is usually more expensive than processed foods and isn’t readily available in many areas — often low-income neighborhoods. Data from 2013 indicate that if every American opted to eat the USDA-recommended serving of vegetables, the country wouldn’t have enough veggies to meet their needs.

Some proposals support cutting unhealthy foods out of SNAP altogether. Others are geared toward giving recipients incentives to buy healthy foods. Advocates of the policies say they would nudge low-income households toward eating more fruits and vegetables, and ultimately improve their health.

“There is validity in both — in trying to incentivize the healthy foods and de-emphasize the more junk food, processed foods,” said Stephanie McBurnett, nutrition educator for the nonprofit Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Defining Nutrition

Food restrictions aren’t just opposed by the left. Rep. Glenn “GT” Thompson (R-Pa.), the top Republican on the House Agriculture Committee, said SNAP health mandates would be hard to carry out because of the gray area about what’s healthy.

“The federal government doesn’t have any definition of what’s nutritional — which is really bizarre — mostly because it’s not easy,” Thompson told reporters at a roundtable discussion.

Thompson said he urged Harris, the appropriations subcommittee chairman, to include language related to a definition of ‘nutritional’ when implementing a pilot program restricting SNAP benefits for some foods.

The appropriations bill (H.R. 4368) didn’t have such a definition — something Thompson said is likely due to the nuance around nutrition.

Republicans such as Thompson also note that most SNAP recipients use multiple forms of payment, like cash or debit cards, with their benefits. That means if recipients can’t buy sugary beverages or processed foods with SNAP benefits, they could still buy them with their own money, said Lauren Bauer, a fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank.

Incentives for Health

Still, providing incentives for healthy eating have been more successful at changing behaviors, Bauer said. More than three-quarters of SNAP recipients in a pilot project offering incentives to shop at farmers’ markets bought more produce than they did before a pilot project, a 2013 study by the Fair Food Network found.

Similar pilot programs have support on both sides of the aisle. The Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program, or GusNIP, funds pilots such as “double up bucks” programs that give SNAP recipients more purchasing power if they buy fresh produce. The program is named for a former USDA leader who supported locally grown food initiatives and healthy eating.

“GusNIP is a proven solution that improves nutrition and health for some of our nation’s most vulnerable,” Cory Booker (D-N.J.), a nutrition advocate on the Senate agriculture panel, said in a statement.

Booker has called for expanding GusNIP in the next farm bill to fund more pilot programs with the goal of improving health outcomes for low-income Americans. He supports legislation that would increase GusNIP funding by billions of dollars.

While GusNIP is popular among Democrats and Republicans alike, increasing its funding will face the same uphill battle as every farm bill program in this reauthorization cycle.

“New spending is going to be hard to come by” in the farm bill, Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said last week, pointing to a tight spending atmosphere in Congress following the recent debt ceiling debates.

To contact the reporter on this story: Maeve Sheehey in Washington at msheehey@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.