2024 Elections Threaten to Wipe Out Last Senate ‘Odd Couples’

By Zach C. Cohen

- Bipartisan Senate delegations showing sharp decline

- Reflects national trend of more polarized electorate

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

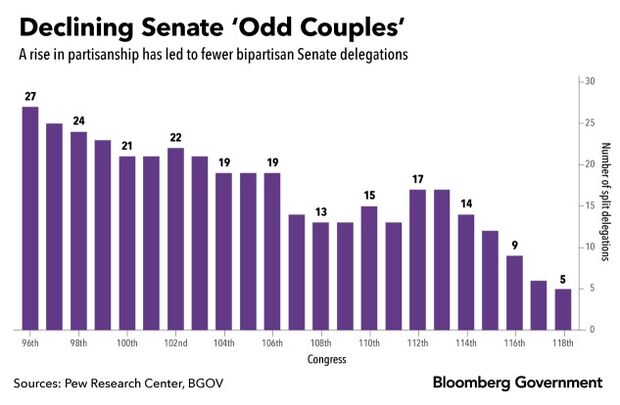

Two decades ago, a quarter of the states had both a Democratic and Republican senator. But in a sign of rising partisanship, the number of states with ‘odd couple’ senators has fallen to five and those rare pairings may be on the brink of extinction.

The 2024 elections could decimate or even wipe out entirely the few remaining Senate delegations split between the two parties. That could unravel one of the last remaining strands of bipartisanship on Capitol Hill in an era of increasingly tribal politics.

“When you have a state that is represented by both parties, that indicates there is a willingness to consider the other side,” said former Sen. Kent Conrad (D-N.D.), who overlapped for two years with Sen. John Hoeven (R-N.D.). “And when you lose that, it just makes it far more difficult to cross the divide to get things done.”

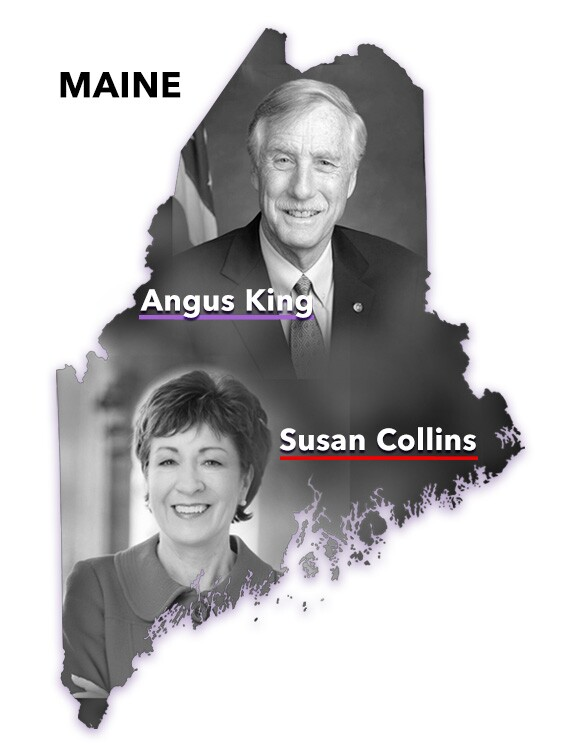

Sen. Angus King (I-Maine), who caucuses with Democrats and represents a split state with Republican Susan Collins, sees value in the pairings.

“I think it’s beneficial to have a foot in each camp,” King said. “I wouldn’t overstate it, but it sometimes comes in handy.”

Currently, only five states are represented in both the Democratic and Republican caucuses: Ohio, Maine, Montana, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

That’s the lowest number of split Senate delegations since the beginning of the direct election of senators over a century ago, according to the Pew Research Center.

What’s more, members of the Democratic caucus in all five of those split states are up for re-election next year. That means the Senate in 2025 could feature even less in-state bipartisanship than there already is, especially with so few opportunities for Democrats to win Senate races in states where Republicans already hold both seats.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if we were down to two or three split delegations” after 2024, said Gary Jacobson, a political scientist at the University of California at San Diego. “Historically, it’s just wildly off the charts, a huge change over the last couple of decades.”

The increasing partisan make-up of states’ delegations reflects a nationwide rise in party-line voting. Presidential contests more often than not determine the winner of concurrent or even future Senate elections, limiting opportunities for members of opposite parties to collaborate to the benefit of their constituents.

“Instead of having people work in a cooperative effort for the benefit both of their state and their nation, they have become almost enemies,” said former Sen. Al D’Amato (R-N.Y.), who served alongside the late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.) for nearly two decades. “It is a tragedy.”

Former Sen. John Breaux (D-La.), a principal and director with the firm Crossroads Strategies, said the shift away from split-party delegations has impacted some lobbying efforts. He said it can make it more difficult to forge bipartisan cooperation on state-specific issues, but it varies by topic.

“If you’re trying to work on a particular state, and it’s all Republicans, and you have a Democratic-type issue, then it’s harder,” Breaux said. “But on the other hand, if you’re lobbying for a labor group and lobbying a state with two Democratic senators, then it makes it easier.”

Home-State Issues

The number of split delegations dropped to its historic low earlier this year when Sen. John Fetterman (D) replaced former Sen. Pat Toomey (R), handing Democrats control of both of Pennsylvania’s Senate seats.

Toomey in an interview said he and Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.) most often collaborated on recommending nominees for federal courts in Pennsylvania.

Senators effectively wield veto power over district-court judges in their states, forcing the two ideologically disparate senators to find consensus picks that would win the support of the White House and the Senate.

“It was difficult at times,” Toomey said. “But the fact that we got along, the fact that we wanted to fill these vacancies with good people, it really enabled us to be very, very productive.”

Bipartisan duos say they can often tag-team to make the best case for their state on more local issues. Collins for instance said she and King “work very closely and well together” on protecting the state’s lobster industry.

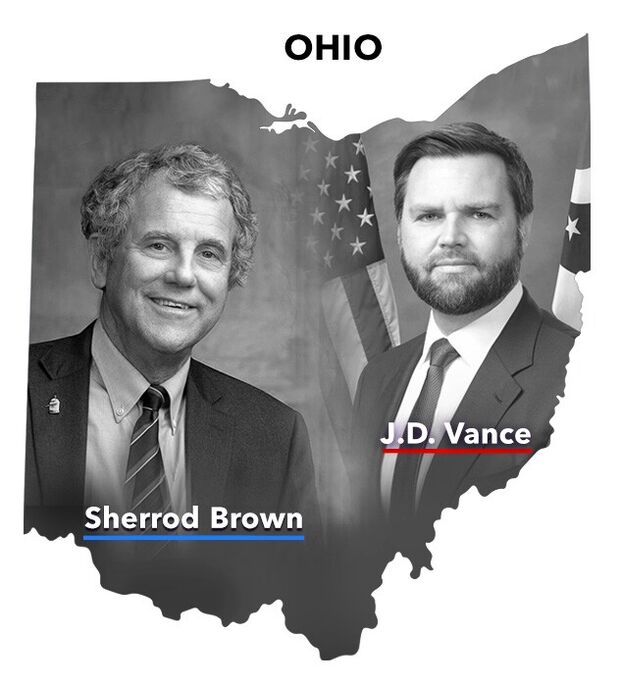

Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) said he and former Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) teamed up over 12 years on a host of issues that overlapped with their political and parochial interests, including infrastructure, fentanyl, and trade. They co-sponsored over 250 bills or amendments together, according to legislative records.

“My focus was always on workers,” Brown said, “and when Republicans want to focus on workers too, we get a lot done.”

That trend continues in Ohio where a February derailment of a freight train carrying hazardous materials has spurred a bipartisan response. Brown and Portman’s successor, Sen. J.D. Vance (R-Ohio), are leading the charge for new railroad regulations that’s gaining support in the split Congress.

“I think we can be effective working together for the people of Ohio, and I think in this particular rail context, it’s been good,” Vance said.

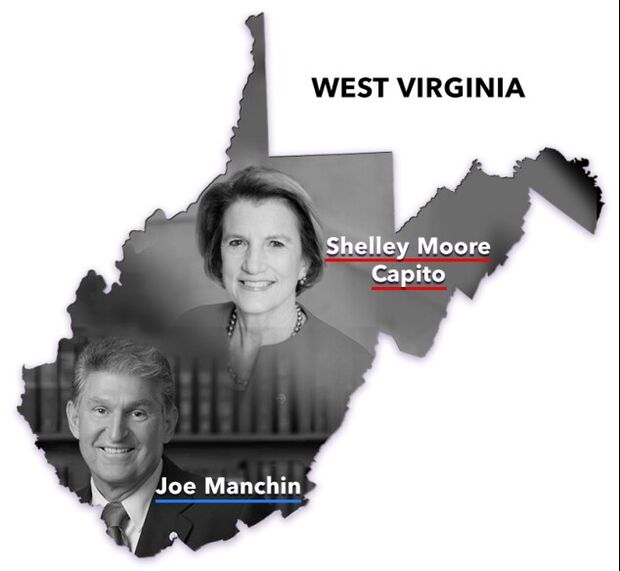

In West Virginia, Sens. Joe Manchin (D) and Shelley Moore Capito (R), both appropriators, have been earmarking powerhouses by jointly requesting and winning hundreds of billions in federal dollars for their state.

Outreach to the presidential administration is also easier with bipartisan delegations, senators say. Regardless of which party holds the White House, the state has a senator of the same ideological persuasion that can press their case.

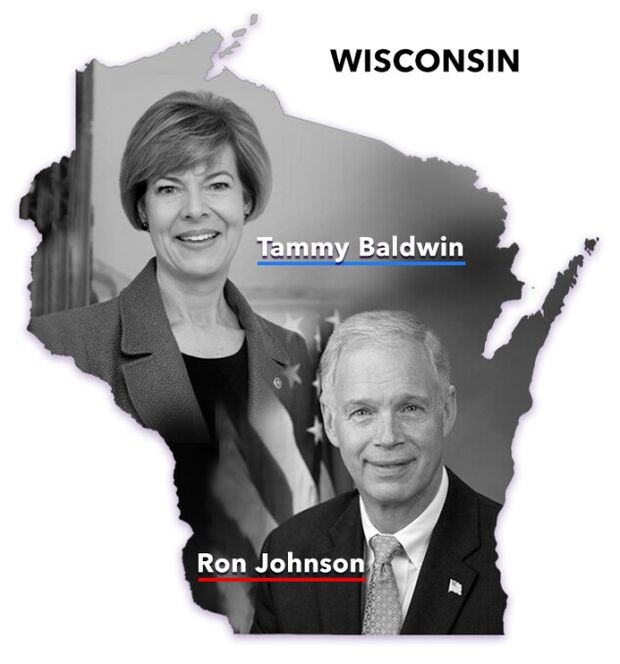

“No matter who’s in office, you’ve got somebody that can appeal to the president to help out your state,” said Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.).

States regularly paired some of the Senate’s most powerful members with a senator of the other party until more recently.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) served alongside former Sen. Wendell Ford (D-Ky.) for 14 years. The two had bitter partisan fights but found common cause in protecting the state’s horse racing and whiskey interests.

The late Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) and former Sen. John Ensign (R-Nev.) famously honored a non-aggression pact when they served concurrently in order to advance Silver State priorities, like preventing the storage of nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain.

“When I joined his office, one of the more frustrating things was being reminded that I needed to follow the ‘don’t criticize Ensign’ rule,” said Jim Manley, who served as Reid’s communications director at the time.

In Iowa, Sen. Chuck Grassley (R) and former Sen. Tom Harkin (D) often collaborated on agriculture issues, responding to natural disasters, and helping senior citizens, even when their voting records diverged during their three decades in the Senate together. They would also defer to each other on recommending judicial nominees in Iowa when their party controlled the White House.

Harkin said that Senate delegations split between the parties are “more helpful to the state, and it’s more helpful to engender a better working relationship in the overall working of the Senate to have that, rather than to have blue states and red states.”

‘Nothing Personal’

The alliance often ends when campaigns begin. Vance and Johnson said they plan to support the eventual Republican nominees to take on Brown and Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wis.), who announced last month that she will seek a third term in a state that barely voted for President Joe Biden in 2024.

King backed Collins’s re-election campaign in 2014 but did not do so again in her blockbuster 2020 race against Democrat Sara Gideon.

“I do not anticipate getting involved” when King seeks a third term next year, Collins told Bloomberg Government.

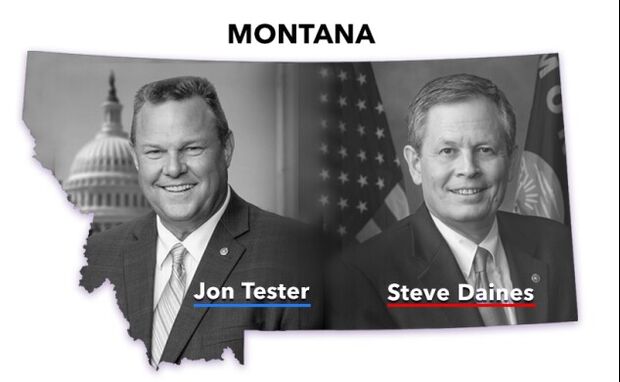

And then there’s Montana, where Sen. Steve Daines chairs the National Republican Senatorial Committee tasked with unseating Sen. Jon Tester (D) in a race that could determine control of the Senate.

That’s a rare set-up. A Senate campaign committee chair hasn’t actively sought to defeat a home-state colleague since 1993, when former Sen. Phil Gramm (R-Texas) chaired the NRSC and former Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-Texas) ousted then-Sen. Bob Krueger (D-Texas).

“It is nothing personal,” said Daines.

With assistance from Greg Giroux and Kate Ackley

Graphics by Seemeen Hashem

To contact the reporter on this story: Zach C. Cohen in Washington at zcohen@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: George Cahlink at gcahlink@bloombergindustry.com; Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.