Meet the Surgeon-Economist at Heart of Democrats’ Drug Price Law

By Alex Ruoff

- Director of Medicare looks to win over drugmakers and seniors

- Agency in midst of hiring, preparing for benefit changes

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Meena Seshamani has a knack for connecting her policy work with the problems many face with the US health system.

When practicing otolaryngology in Georgetown, she saw a patient with a growing mass on her neck. The woman told Seshamani—a practicing surgeon and economist—her insurance wouldn’t cover the surgery. If the patient had cancer, it could cripple her financially.

But Seshamani, now the director of the Center for Medicare, knew the Affordable Care Act’s annual open enrollment was soon; in fact, a few years earlier, she’d been a central figure in implementing the law. She told the patient she could get new, likely subsidized insurance — even with a preexisting condition.

“To me it’s just such an incredible privilege to be able to impact change both on that system level — and then really see tangibly how that impacts a particular person,” she said in an interview.

Seshamani, 45, now faces a new challenge linking policy to practice. She must follow through on the White House and Democrats’ promises that their partisan climate, tax, and drug pricing law, dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act (Public Law 117-169), will actually reduce the costs of prescription drugs.

For Seshamani, the goal is simple: make medicines cheaper for people on Medicare, the federal health insurance program for people aged 65 and over, and for the disabled.

“Success is being able to make prescription drugs more affordable for people with Medicare,” she said.

Seshamani stands as a central figure in the Biden administration’s effort to implement the law. She must oversee an expansion of Medicare benefits — and the agency itself — to get drug prices down, even as drugmakers attempt to sidestep her efforts, lobbyists and industry insiders say. Seshamani also faces the close eye of congressional oversight on her work.

“No doubt you’re going to see maneuvering from pharma to mitigate any impact of this,” said Rob Smith, managing director at Capital Alpha Partners, a public policy consulting firm in Washington. “It’s going to be a big lift for HHS.”

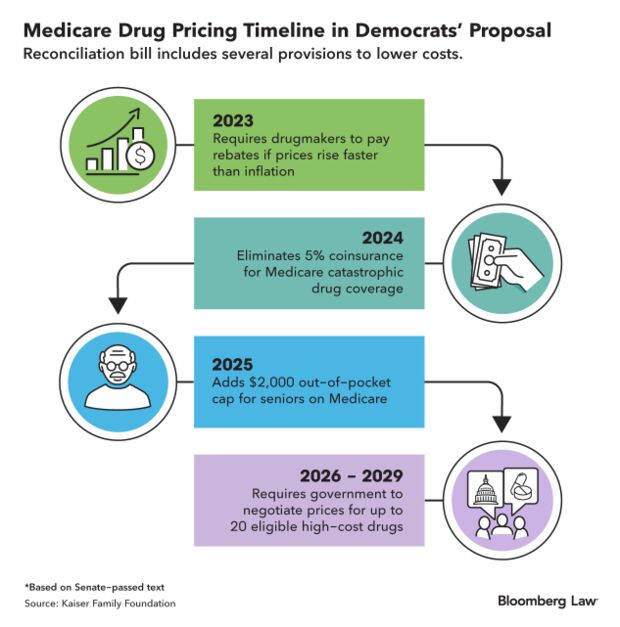

The drug pricing law has been criticized for being both too much and not enough. Its provisions are largely focused on Medicare: the agency will cap what seniors on the program pay for drugs at $2,000 per year starting in 2025, it will negotiate for lower prices on 10 drugs starting in September, and it will redesign Medicare’s drug benefit in a host of ways.

While these are major changes for Medicare, they’re also far short of the sweeping use of government power to demand cheaper medicines that Democrats have campaigned on for years. Private insurance plans won’t directly benefit from the law’s cap on annual price increases, or its limits on insulin copays.

Supporters hope some of these policies will help lower prices for people with private insurance, but that’s yet to be seen.

Changes for Medicare

Medicare must enact three significant prescription drug policies at the beginning of next year: Inflation rebates — or pegging drug price increases to inflation — will begin for Medicare Part B, which covers various outpatient services; people on Medicare will no longer have copays for vaccines; and Medicare will cap out-of-pocket costs for insulin at $35 per month.

The agency faces a mountain of work ensuring seniors aren’t paying more than they should, telling seniors about these new benefits, and setting up a system to collect rebates from drugmakers.

Those who’ve worked with Seshamani say she’s uniquely qualified for the job: she played a significant role in implementing the Affordable Care Act during the Obama administration. She then went into senior leadership at MedStar Health, the largest health-care provider in the Maryland-D.C. area. She’s been in Democratic health policy circles for decades and was part of the Biden transition team at the Department of Health and Human Services.

For much of her career, Seshamani has alternated between leadership roles and practicing medicine as a head and neck surgeon — often keeping both going. She also holds a Ph.D. in Health Economics from the University of Oxford.

“She knows how to bring together her surgeon brain with her economist brain,” said Natalie Davis, CEO of the nonprofit advocacy group United States of Care, where Seshamani served as part of the Founder’s Council. Davis also worked at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services on ACA implementation. “One thing she does is: if doesn’t know something, she knows how to surround herself with people who know the right answer.”

Drugmaker Talks

Seshamani said she’s begun meeting with health plans, pharmaceutical companies, and seniors covered by Medicare to start implementing the law. Talks with drugmakers have been productive, focused on where the industry can benefit from things like caps on out-of-pocket costs, she said.

“We’ve engaged in really productive conversations, hearing about where there are concerns, questions, where there are opportunities,” Seshamani said. “We’ve also heard from manufacturers how much this is going to improve access to some of their therapies.”

Read More: Haggling With Pharma: Medicare Drug Price Negotiations Explained

A spokesman for CMS declined to name any companies but noted the agency is speaking with individual drug companies and trade associations for “technical meetings.”

Seshamani last Monday spoke at a conference hosted by the Association for Accessible Medicines, a trade association for generic drug manufacturers, according to the group’s website.

The agency is also trying to set up ways to collect data from drugmakers for inflation rebates and future drug price negotiations, information about company profits, and spending on research and development.

Seshmani is looking for nearly 100 people to fill out the ranks of the proposed Medicare Drug Rebate and Negotiations Group, a body within HHS to head key drug pricing topics. The Center for Medicare now has 775 full-time employees and a budget of $1.1 trillion.

“We’re looking for people with expertise in pharmaceuticals, economists, analysts, people with management experience,” she said. “There is a breadth of expertise that we want to make sure that we bring in so that we can implement the law in the most thoughtful manner possible.”

HHS officials are also looking backward, getting advice from those who worked on implementing Obamacare and on the creation of Medicare’s drug benefit nearly 20 years ago.

There are echoes of the implementation of Medicare Part D, said Chris Jennings, a policy adviser for Democrats. For one, HHS will have to stand up a major new health program as the sitting president prepares for a reelection battle, he said — which will likely put any major policy work, particularly on drug pricing, under serious scrutiny.

Mark McClellan, the founding director of the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke University and head of CMS during the implementation of Part D, said he talks regularly with Seshamani, both about his center’s research on Medicare and the program’s benefit structure.

McClellan said the IRA is the “biggest change in Medicare coverage and payment since” the creation of Part D and noted it will require taking in a lot of public comment.

“If you want a sustainable program that will survive from one administration to the next, it needs to go through a process that is sound and predictable,” he said. “You need to get feedback early.”

Strict Oversight

Seshamani and the whole of HHS will do this drug pricing work under the eye of a Republican-controlled House, which will seek to paint the IRA as more harmful than beneficial. That means agency officials will face critics responsible for providing them funding for at least the next two years.

Read More: House Panel Will Punch Back on Biden Energy, Health Policies

“Whether you’re covered by Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, or are uninsured, you’ll be paying more for your medications as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act if these new cures are developed at all,” Republican Reps. Michael Burgess (Texas), Andy Harris (Md.) and Brad Wenstrup (Ohio), the heads of the GOP Doctors’ Caucus, wrote in a recent op-ed. The trio claimed that higher launch prices for drugs will offset any other reduction in prices from the new law.

Democrats in Congress say they, too, will be watching implementation of the drug pricing law closely; many hung their political future on its success in making medicine cheaper in the US.

“When people see the benefits starting next year, it will become more manifest to them how important it was to vote for it and to see more,” Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.) said.

If those benefits don’t materialize, the Biden administration and Democrats may face backlash from the public, political consultants warn.

“If the government says they’re going to reduce prescription drug prices, then the government should be held responsible for that,” Bill Hoagland, senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center, said. Hoagland was a policy adviser on budget and financial matters for former Senate leader Bill Frist, who was instrumental in creating Medicare’s drug benefit.

“Before, you could always blame the drug companies, but now you can blame the government if those prices don’t go down,” Hoagland said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.