Republicans Plan to End Proxy Voting Even as They Use Practice

By Emily Wilkins and Zach C. Cohen

- Some GOP lawmakers say remote voting is ripe for abuse

- Members also cite illness, pregnancy, Covid for such votes

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

House Republican lawmakers have relied on proxy voting the last two years while they were battling cancer, caring for loved ones, and giving birth.

But if the party wins control of the House in the 2022 elections, the GOP is determined to do away with the practice put in place by the Democrats to deal with health concerns stemming from the Covid-19 virus. Instead of allowing a colleague to announce their position on bills and amendments, members would once again have to show up in person in the chamber to have their votes counted.

Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) has long opposed proxy voting, waging an unsuccessful legal fight up to the Supreme Court to fight the practice GOP lawmakers say is ripe for abuse and an abdication of governing responsibilities.

“There’s no question in my mind that Speaker McCarthy will not allow proxy voting. Not even like a ‘maybe,’” said Rep. William Timmons (R-S.C.) “Never, ever, ever, ever. Period.”

Democrats adopted the precedent-breaking procedure in May 2020 to reduce physical interactions that could spread Covid-19 between members and staff flying in from different parts of the country.

Under the procedure, a member has to submit a letter designating a colleague to record their position, which is announced in the chamber during votes that otherwise are conducted by electronic device.

House Republicans, who are well-positioned to win the majority in the November election, could opt to simply let the proxy voting expire or vote to end it with a new resolution. The voting practice was renewed when the new Congress met in January 2021, must be reauthorized every 45 days, and was extended through March 30 by Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.).

McCarthy has the backing of his leadership on scrapping the option. House Minority Whip Steve Scalise (R-La.) told reporters that proxy voting “hurts the legislative process when we’re not meeting in person.”

House Republican Conference Chair Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), who cast more than 100 proxy votes including some while on maternity leave, said in an interview that she opposes the rules set by House Democrats and predicted Republicans would eliminate them if the chamber flips.

“We are committed as Republicans to returning back to in-person working,” Stefanik said.

Theory Versus Practice

While Republicans oppose proxy voting in theory, many have embraced it in practice. In 2020, 160 Republicans signed on to McCarthy’s lawsuit against proxy voting. By the end of 2021, roughly 70% of the original plaintiffs still serving in Congress either voted by proxy or served as another member’s proxy at least once, according to a study from the Brookings Institution.

After the legal challenge was dismissed in lower courts, only McCarthy and Rep. Chip Roy (R-Texas) signed on to the appeal to the Supreme Court. The justices rejected the challenge in January.

House GOP Leader McCarthy Is Rejected by U.S. Supreme Court Over Proxy Voting

Roy said the general consensus among Republicans is to get rid of proxy voting. He said letting members vote remotely through a form other than a proxy in certain circumstances could be “worthy of debate,” but still he said he wouldn’t be supportive.

“I think it’s garbage,” Roy said. “Congress met though WWII, Congress met through the Civil War, and we’re going ‘Oh my god I’ve got to be home.’ Do your damn job. Come here and vote.”

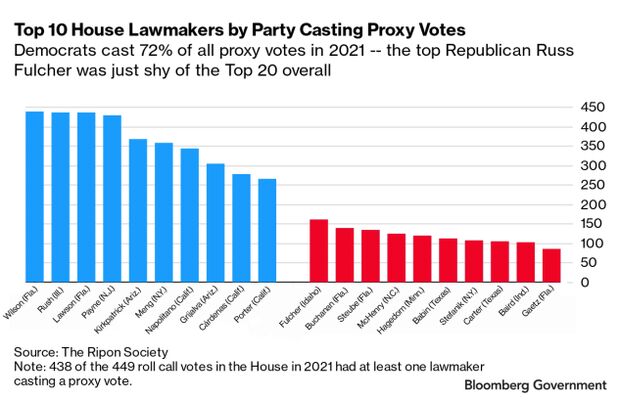

An analysis of proxy votes in 2021 by the center-right Ripon Society found Democrats were responsible for 72% of all proxy votes in 2021. Among Republicans, Rep. Russ Fulcher (R-Idaho) cast the most proxy votes, with 160 votes, according to the study.

Fulcher opposes the practice but said he relied on it after he was diagnosed with renal cancer. Fulcher, who announced in December he was cancer-free, said his situation was “rare.”

“Overall, the proxy policy has proven to be too ripe for abuse,” he said in a statement. “Even in the short term it has been available, some Members have voted while on a campaign tour or from recreational locations.”

Rep. Vern Buchanan (R-Fla.), who voted by proxy nearly 140 times, the second most of Republicans in 2021, said he relied on the practice when he had Covid and to deal with other issues, but hoped to see the practice eliminated.

“In terms of moving forward, I think we’ll move back to operating the way we did,” he said.

‘Hell for Lobbyists’

Of more than a dozen House Republicans interviewed, only Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) said he favored keeping the current proxy-voting practice while John Carter (R-Texas) said he could see it used in limited circumstances.

“I’m for remote voting because it makes life hell for lobbyists,” said Gaetz. “If we use proxy voting, we get to spend more time with our constituents and less time in this awful place.”

Carter said he used proxy voting when he took care of his wife while she was sick. He agreed lawmakers needed to be in Congress to vote and criticized those who abused the rule. But he also said technology allows members to make informed decisions on how to vote, even if they can’t vote in person.

“If you have a serious family emergency or some kind of emergency in your district, like a hurricane came in or stuff like that, you ought to be able to proxy vote,” Carter said.

Rep. Guy Reschenthaler (R-Pa.) said although he wants to do away with proxy voting, as long as Democrats are using it, he doesn’t want Republicans to unilaterally disarm.

“If those are the rules, I’ll play by the rules, because I don’t want to give the opposition an unfair advantage,” Reschenthaler said in an interview. “The danger of proxy voting is this: at a certain point the argument can be made that this institution’s not relevant.”

“People would say we should stay at home in our districts and proxy vote indefinitely,” he added. “What that would do is it would empower leadership and diminish the voice of the people at home.”

Andrew Small also contributed to this story.

To contact the reporters on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com; Zach C. Cohen in Washington at mailto:zcohen@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.