Automakers Pushed to Fight Drunk Driving in Infrastructure Bill

By Lillianna Byington

- Infrastructure bill with safety provisions heads to Biden

- Implementation to be determined by Transportation Department

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Katie Snyder Evans was heading home in 2017, after visiting her premature twin girls in the hospital, when a car going 95 miles an hour with a drunk driver at the wheel flew over a median into her lane, killing her.

Ken Snyder, Katie’s father, is among those who have lobbied Congress for years to mandate technology, some already available, that could have prevented deaths like his daughter’s. Now the passage of the infrastructure bill (H.R. 3684), which President Joe Biden will sign into law Monday, has given him and other advocates what they asked for—a provision calling for requirements that new cars be equipped with whichever technology best prevents drunk-driving deaths.

“This is forcing them to do something that they’ve known how to do for years but have chosen not to do,” Snyder said of the automakers. “It’s frustrating to those of us who have lost loved ones.”

The infrastructure bill also includes calls for regulations around other causes of accidents, including automatic emergency braking in cars and large trucks, rear-underride guards on trucks, and improved headlights. They come as highway fatalities are on the rise. But many of the provisions fall short of what advocates had lobbied for, and the safety advances could take many years to become commonplace on roads.

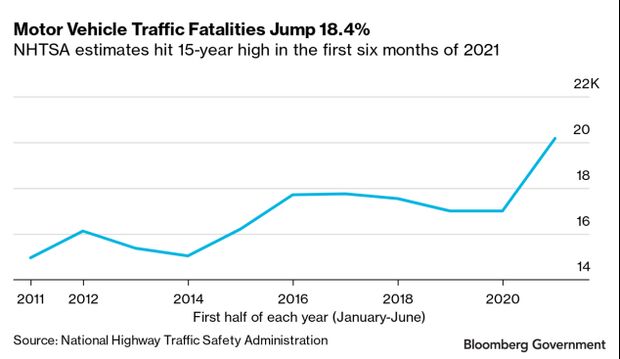

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimated 20,160 people died on U.S. roads in the first half of 2021, up 18.4% over last year. Impaired driving is among the major causes for that, with an average of more than 10,000 people dying every year in drunk-driving crashes over the last decade, according to NHTSA.

“Now comes the next phase to deliver results,” said Sen. Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.), who is a survivor of a drunk-driving crash and worked on the drunk-driving legislation in the bill.

TBD: Technology Required

Under the legislation, NHTSA would decide the technology required in new cars within three to six years. Carmakers would then have two to three years to implement it. That adds to the backlog for an agency that has already failed to meet congressional deadlines to publish some regulations and is now in its fourth year without a Senate-confirmed administrator.

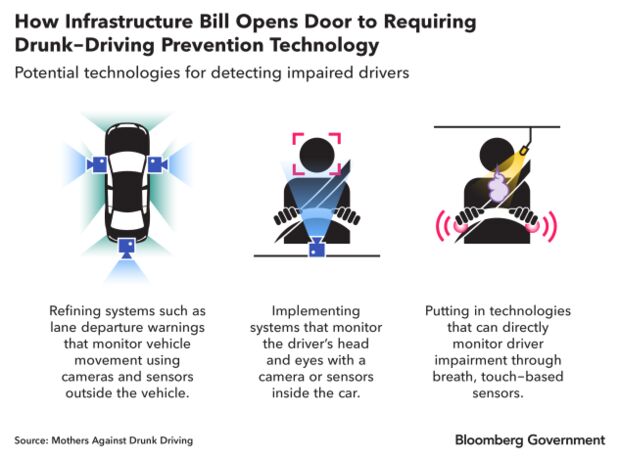

Mothers Against Drunk Driving in a recent report identified 241 examples of drunk-driving technology available now or being developed that could be required in cars. They include existing systems that could be updated to detect signs of impaired driving, like lane departure warning and attention assist, as well as technology inside the car that monitors the driver’s head and eyes with a camera or sensors, or breath and touch-based sensors.

Carlos Monje, undersecretary for policy at the Transportation Department, said NHTSA will go through the process with notice and comment, working with industry and safety advocates “to make sure we get it right.”

“The number of traffic deaths are increasing. We know that the main factors there are speed, distraction, and impairment, and we plan on addressing all those issues,” Monje said.

Using technology to prevent drunk driving isn’t a new concept. About 30 states require ignition interlocks, or in-car breathalyzers, to be installed in the vehicles of people convicted of a first drunk-driving offense.

The technology that NHTSA decides to implement and the timeline of the requirement will determine the effectiveness of the infrastructure bill’s provision, advocates say.

Automakers have been reluctant in the past to move forward on new safety technology, often saying more research is required. In 1985, after the then-transportation secretary sought state laws requiring the use of seat belts, a mass lobbying effort from industry popped up across the country to fight it. Carmakers also fought air bag mandates. Thousands of lives have been saved annually because of seat belts and air bags, NHTSA estimates.

The drunk-driving provisions in the infrastructure bill passed over the objections of the American Beverage Institute, a lobbying group for the restaurant industry, which called them “unreliable gimmicks to satisfy anti-alcohol lobbyists.” It predicted the technology could cause more than 3,000 false readings a day.

But some companies have already moved forward with it. Volvo Car AB announced in 2019 that it was going to deploy in-car cameras to prevent intoxicated and distracted driving.

“I will not celebrate until we have it implemented,” Snyder said. “Until it’s actually on cars and in place working and saving lives, I can’t stop.”

Slow Rollout

The Automotive Coalition for Traffic Safety said earlier this year that its first product with new alcohol-detection technology, which is a small sensor that drivers breathe into to detect alcohol concentration, will be available for licensing in commercial vehicles in late 2021. It was developed after research and testing by the Driver Alcohol Detection System for Safety Program, which is a partnership with industry and NHTSA.

John Bozzella, CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, said the group appreciates lawmaker and stakeholder efforts “to advance a legislative approach that provides NHTSA the ability to review all potential technologies as options for federal regulation” and to decide “whether any specific technologies meet the standard for consumer vehicles.”

Because the requirement would only apply to new cars, and the average car on the road is 12 or 13 years old, it will take time for the rollout process to be comprehensive, said Russ Martin, senior director of policy and government relations for the Governors Highway Safety Association.

“The implementation of the legislative requirements by those agencies will be key to the success of the legislation,” said David Harkey, president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and the Highway Loss Data Institute. “The final measure of success will be: do we reduce the fatality numbers?”

Many of the safety provisions in the bill were crafted and passed out of the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee earlier this year as part of the five-year reauthorization of surface transportation programs that ended up in the larger infrastructure bill.

Truck Safety Changes

The infrastructure bill also includes provisions to stop non-alcohol related accidents.

When a truck hit Marianne Karth’s car in 2013, spinning her vehicle around and sending it backwards into the back of the tractor trailer, the truck’s rear underride guard came off. The back of her car—where her two teenage daughters, AnnaLeah and Mary, were sitting—went under the truck. The girls were killed, while Karth and her son, who were sitting in the front seat, survived.

“It was a horrific crash,” Karth said. “But it wasn’t that the truck was bigger than us, because I was in that same crash with the big truck. It was the underride that we learned was the problem.” Karth has since had hundreds of meetings with lawmakers and staffers advocating for underride legislation.

The infrastructure bill calls for updated regulations on rear underride guards but puts the onus on the Transportation Department to decide whether it will mandate the strongest guards.

“Hopefully, they will require that, but if they don’t, it’ll be like a sham, like a totally useless revision that will still leave the potential for trucks, even new trucks, to be out in the road that people can die under,” Karth said.

The bill also requires research on the feasibility of side underride guards, which the industry has opposed mandates on. Dan Horvath, vice president of safety policy at the American Trucking Associations, said rear underride guards have been installed on trucks for a number of years and the group has been supportive of strengthening standards around that.

“With anything, we prefer the regulatory approach, which allows notice and comment,” Horvath said. “It gives stakeholders the ability to provide comment and feedback.”

The provision seeking regulation on automatic emergency brakes falls short of requiring them on all types of trucks as advocates sought. Joan Claybrook, a former NHTSA administrator, said the Transportation Department should view the directives “as a floor and not a ceiling for what can be achieved.”

“Like air bags, which I worked on in the 1970s and 80s as administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, AEB is a game-changing, life-saving technological advancement,” she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Lillianna Byington in Washington at lbyington@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Fawn Johnson at fjohnson@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.