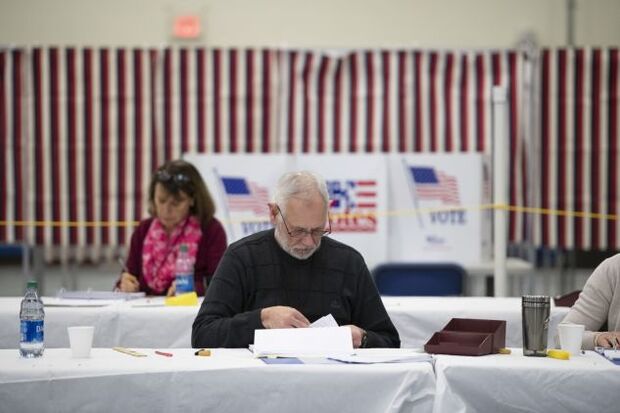

Mail Voting Opens Door to Minority, Student Disenfranchisement

By Emily Wilkins

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Minorities, young adults and those with disabilities face barriers to voting by mail as states rush to prepare for holding elections as safely as possible.

The impact of long-existing issues with voting by mail wasn’t as perceptible in previous elections because only a fraction of the electorate in most states utilized absentee ballots. The coronavirus is expected to change that in November, but state officials are making decisions now on how voters will cast their ballots in the general election, as well as in dozens of primaries over the next several months.

Organizations advocating for voters, blacks, Hispanics and college students say voting-by-mail is an important option. But a number of state-level policies can make it harder for voters to request and send a ballot that won’t be rejected. While these policies impact all voters, they can be a bigger burden for some, said Aneesa S. McMillan, director of strategic communications and voting rights with Priorities USA, a super PAC aligned with presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden.

“Everybody that was on the margins when we were trying to get folks to show up in person, those people remain on the margins,” she said. “I would argue those gaps increase because of the nature of the pandemic.”

To address their concerns, lawsuits have been filed in dozens of states. Key presidential and congressional battlegrounds, including Pennsylvania, Michigan, North Carolina and Florida, all have ongoing lawsuits, some from voters rights organizations, others from Democratic-party aligned groups.

Republicans have opposed many of the proposed changes. One of the biggest concerns, said Jessica Furst Johnson, a former National Republican Congressional Committee general counsel, is that a rush of lawsuits could cause even more confusion among voters about how the mail-in process works and eventually lead to more contested elections.

“A lot of these very reactionary opportunistic calls for change are going to do nothing but upend established election processes and result in great confusion to voters,” she said.

Different Groups, Different Hurdles

Voter rights advocates and attorneys identified several groups most likely to struggle with mail-in-voting, although the reasons why vary from group to group.

“Mail impacts different communities differently,” said Seth Bringman, a spokesman for Fair Fight Action. “Voting by mail can be more difficult for some voters than others.”

Native Americans living on reservations might not have a mailing address. College students who registered at an address on or near a now-closed campus may have relocated back home.

Lower-income voters tend to move more, meaning their address might not match the one to which their ballot is sent. Coronavirus is expected to aggravate displacement, as high unemployment forces people to move out of their homes, said Vanessa Cardenas, a senior adviser for LULAC, an advocacy group for Hispanics. Black and Hispanic median household incomes have been the lowest of any race or ethnic group for the past 50 years, according to the Census Bureau.

“People are losing their homes, they cannot afford to pay rent, they cannot afford to pay their mortgage, so they’re becoming more of a transient community,” Cardenas said.

There’s also a security that comes with in-person voting, an important factor for historically disenfranchised groups, particularly blacks.

Once voters receive their ballot at a polling place, the chances it will be thrown out are “vanishingly small,” said Marc Elias, the lead attorney for the Democratic Party’s voting rights effort.

When a voter mails in a ballot, there’s a chance their ballot will be rejected for a variety of reasons depending on the state — mismatched signature, no witness for the signature, no signature on the envelope. Nearly every state rejects a small number of ballots, usually less than 1%, according to MIT’s Elections Performance Index.

A study of mail-in ballots during Florida’s 2018 general election found several discrepancies based on age and race. Compared to voters 65 and older, voters 21 and younger were five times more likely to have their ballots rejected, and voters between the ages of 22 and 25 were four times as likely.

Black and Hispanic Floridians who voted by mail were twice as likely to have their ballots rejected as white voters, according to the study from political science professors at the University of Florida and Dartmouth.

While 1.2% of the 2.6 million mail ballots were rejected, the report warned that those 31,969 rejected ballots should be taken seriously given former Gov. Rick Scott’s (R) winning margin over then-Sen. Bill Nelson (D) was 10,033 votes.

“If you knew your ballot was twice as likely as someone else to be rejected, you would have less trust,” Elias said.

Universal Fix

While not every issue can be addressed with legal action, lawsuits from voting rights organizations and Democratic-aligned groups are addressing policies in dozens of states.

Some legal action has focused on making sure there are in-person polling places for those with disabilities preventing them from filling out a ballot without assistance, or for those who can’t speak or read English and don’t live in areas where the population requires a ballot to be translated.

The ACLU and NAACP are also suing Louisiana for requiring a witness signature on ballots cast by mail, a burden the groups say will impact all voters but poses a higher threat to blacks given they make up the majority of coroanvirus deaths in the state while being only a third of the population.

Native Americans living on reservations sometimes don’t have house addresses and could live far away from the nearest post office. To make it easier for them to mail their ballot, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit challenging a Montana law that reduced the number of ballots one person can collect to drop off to 6 from 85.

Republicans have pushed back against several of the policies, such as ballot collecting.

Other lawsuits in battleground states including Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Florida focused on ensuring four “pillars” of vote-by-mail, as Elias describes them: free postage; counting ballots postmarked by election day, even if they arrive after election day; ensuring states that use signature matching train officials and provide the option of fixing the ballot; and allowing organizations to collect and deliver sealed ballots.

Some of the lawsuits began before the pandemic started as part of a wider effort to help people vote, said Sophia Lin Lakin, deputy director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project. But the coronavirus has heightened the urgency around ensuring vote-by-mail is as accessible as possible.

“The pandemic makes the process and procedures around making sure your vote is counted much more pressing,” she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergtax.com; Kyle Trygstad at ktrygstad@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.