Inmate-Scholars Do So Well on Pell Grants That U.S. May Add More

- Allowing federal aid for prisoners weighed for education bill

- Those sentenced to life might be excluded from program

At Jackson College in Michigan, one group is doing exceptionally well compared with their peers: the students in prison.

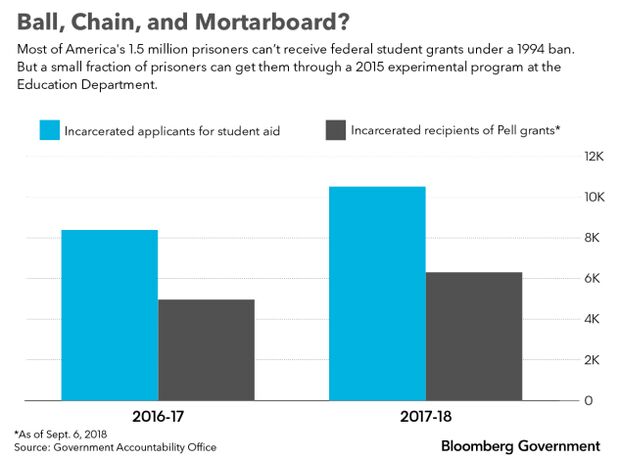

The students at Jackson College are part of a small group of incarcerated individuals—about 8,800 students at 64 schools—receiving Pell grants through an experimental Education Department program.

Last year, 621 inmates enrolled in the college for the first semester of 2018, taking classes, doing homework and studying behind bars. Their average GPA was 3.36, higher than the college’s overall average of 2.71. When the dean’s list came out, almost a third of the students on it were in prison.

“They just take the classes very, very seriously,” said Jeremy Frew, vice president of student services at the college. “They see there’s an opportunity that they might not have had.”

Most of America’s 1.5 million prisoners are prohibited from receiving Pell grants under a 1994 ban Congress imposed at the height of a tough-on-crime era.

A quarter of a century later, times have changed. Members of Congress in both chambers and parties, as well as the Trump administration, support expanding the nation’s largest grant program for low-income students to prisoners who meet the criteria. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced in May she would pave the way for more schools and students to participate.

Some top officialsare considering removing the ban only for prisoners who will be released. More than a dozen advocacy groups and colleges are pushing to include all prisoners under a “clean” lift of the barrier. They say it will help prisoners find work when they are released, and improve the climate and safety inside the prisons. What lawmakers decide will shape how well expanding Pell grants to prisoners ultimately work.

“The advocacy community are trying to raise the arguments on why a clean lift will be beneficial and increase the number of positive outcomes, ” said Daniel Landsman, director of federal legislative affairs with FAMM, a national criminal justice advocacy group. “It might be an uphill battle to get life without parole folks in, but I think it’s one worth looking into.”

Pros and Cons of Cons

Earlier this year, Democratic lawmakers introduced for the third time legislation (H.R. 2168, S. 1074) to give inmates Pell grants. This year, several Republicans came on board—Reps. Jim Banks (Ind.) and French Hill (Ark.) in the House and Sen. Mike Lee(Utah) in the Senate.

“If we can take this population and give them a step up by preparing them for leaving prison with skills and a better outlook on life, we reduce recidivism rates and society is much better off,” Banks said.

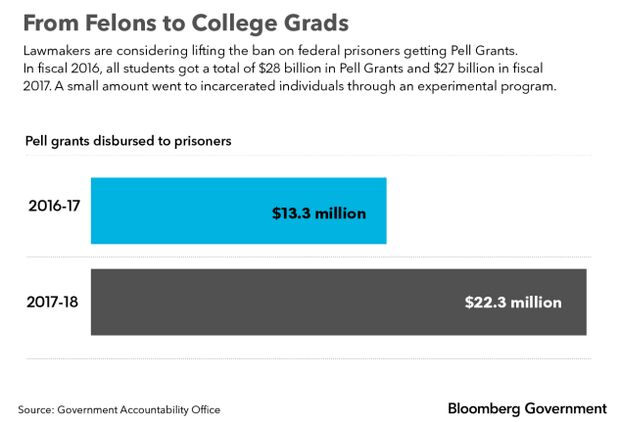

An estimated 463,000 prisoners would be eligible for the grants, based on their income and if they completed high school, according to the the Vera Institute. But even in the unlikely scenario where all prisoners received a grant in the same semester, the Vera Institute estimated the program’s costs would increase by less than 10%.

Lee, the sole Republican on the Senate’s bill, said lifting the ban is the logical next step after lawmakers passed a bipartisan criminal justice bill in December 2018 (Public Law 115-391).

Lawmakers and advocates want the legislation included in an update to the higher education law (Public Law 110-315)currently being negotiated by Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn) and Patty Murray (D-Wash.), the top lawmakers on the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee.

Alexander leans toward Pell grants with limits resembling the Education Department’s program: only for inmates who will be released. The Trump administration has proposed similar restrictions.

The majority of prisoners will be released, and a widely cited a 2002 Bureau of Justice Statistic report found 95% will return to society. Of those, about 40% will return to prison through committing new crimes or breaking parole. Yet those who take educational programs while in prison reduce their odds of returning to prison by 43%, the RAND Corp. found in 2014.

“Most prisoners, sooner or later, are released from prison, and no one is helped when they do not have the skills to find a job,” Alexander said in a statement. “Making Pell grants available to them in the right circumstances is a good idea.”

All or Nothing

Advocacy groups say including individuals serving life sentences leads to good behavior and safer prisons. Lifers help mentor younger inmates and develop a facility’s culture. After the Michigan Department of Corrections began offering some inmates Pell grants — like the ones in Jackson — misconduct at the student housing unit decreased by 90% compared with a non-student housing unit.

“Regardless of whether someone is going to be released, their participation in a program underscores the importance of that program in the facility,” said Julie Ajinkya, vice president of applied research at the Institute for Higher Education Policy. “Making it so you’re not excluding people from the outset is going to set that program up for success.”

Withholding Pell grants for those who won’t be released subverts the purpose of the aid, said Gerard Robinson, the executive director for the Center for Advancing Opportunity.

“When you make it a social crime issue, you then take the education human-development, human-dignity target off the table,” he said.

Ban Supporters

Many Republicans want the ban kept in place. About four dozen Republicans opposed the 2018 criminal justice law,in part because they felt it was too lenient on certain types of criminals.

Rep. Virginia Foxx (Va.), the top Republican on the Education and Labor Committee and a fiscal conservative, opposes expanding Pell grants, noting that many states already fund education in prison.

Advocates and lobbyists blame misinformation for some of the opposition to the prison Pell grants. The need-based grants are entitlements given to all applicants who meet eligibility criteria.

Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-Calif), who co-sponsored a bill last Congress to block any federal funding for prisoners, said he supports teaching prisoners basic skills, but didn’t want low-income students to “miss out” on grants because they went to prisoners. Pressed further, he voiced skepticism but said he could be open to a limited expansion.

“I’d be more inclined to look and see what kind of prisoners are we extending it to, what kind of crime are they in for,” he said.

Center of Debate

Advocates say they may need to strike a compromise.

“I don’t think some Republicans are going to shy away from ‘no ban,’” Robinson said. “But some of them may say, ‘If you exclude certain groups or include technical and job training solely, maybe I’m interested.’”

Discussions are continuing, said Heather Rice-Minus, vice president of government affairs at Prison Fellowship. While Lee is the only Senate Republican supporting a clean lift, Rice-Minus said others in his party agree with him but are waiting for Alexander’s proposal and political cover.

“It doesn’t change the dates someone comes home,” she said. “It changes the person who comes home.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com; Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergtax.com