Cyber Agency Resists Regulator Role as Bills Aim to Expand Power

- Reporting hacks to cyber agency required by bills in Congress

- CISA would get subpoena power; director emphasizes partnership

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

High-profile cyberattacks on critical businesses like Colonial Pipeline Co. have lawmakers pushing for mandatory cyber incident reports that would boost the regulatory power of a three-year-old cyber agency—a role the agency is reluctant to inherit.

The recent surge in cyber and ransomware attacks on critical infrastructure operators ranging from software providers to meat-processing plants has spurred Congress and the Biden administration to increase the cyber protections of certain privately-owned industry sectors essential to the country’s security, health, and safety. Just this week, the administration and allied countries arrested individuals tied to a Russian-linked ransomware group that attacked the U.S. earlier this year and seized $6 million in ransom payments.

House and Senate bills (S. 2875; H.R. 5440) advancing through Congress would require critical industries—like energy companies and hospitals—to report cyber incidents to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which was created in 2018. If passed, the legislation has the potential to give CISA more regulatory authority.

While the legislation has the backing of CISA Director Jen Easterly, she stressed that she doesn’t want it to reshape the agency’s identity.

“At the end of the day, I don’t want CISA to be a regulator,” Easterly said.

“I think that becoming seen as a regulator fundamentally changes the magic of CISA, which is the collaborative partnerships that make us so effective in the space,” she said in an interview. “This is all about sharing signal so that we can help raise the baseline of the cybersecurity ecosystem.”

At the same time, Easterly wants enforcement oversight beyond subpoena power provided in the bills, including the authority to fine companies that don’t report cyberattacks to the agency.

Existing Regulatory Powers

The legislation would direct CISA, housed in the Homeland Security Department, to issue rules defining what types of cyber incidents must be reported and which infrastructure operators would be affected. Lawmakers want the government to know when an operator is hit by a cyberattack so it can quickly assist in recovery and notify others if it’s a widespread incident. The private sector operates 85% of critical infrastructure including the transit industry, hospitals, and water facilities.

Read More: Russia-Linked REvil Hackers Hit With Arrests by U.S., Allies

The measures are in response to an uptick in cyber and ransomware attacks in the last year. The Colonial Pipeline attack forced a shutdown of nearly half of the East Coast’s fuel supply and led to long lines at gas stations throughout the region. A massive cyberattack on SolarWinds Corp.’s software in 2020 hit more than 100 companies and at least nine federal agencies.

“I am hoping that people aren’t looking at this as yet another regulation, but really something that’s good for all of us because frankly, this has to be about collective defense,” Easterly said.

CISA already has some limited regulatory authorities. It manages the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards that regulate facilities to reduce the risk that terrorists access hazardous chemicals.

“While CISA is best situated as a convener of information sharing and a center of excellence for cyber expertise, they are also a current security regulator as well,” Brian Harrell, CISA’s former assistant secretary for infrastructure protection during the Trump administration, said in an emailed statement.

“So, while not their sweet-spot, there is an existing framework to use,” Harrell said.

Regulator or Partner?

Some fear such new regulatory authorities would change CISA’s dynamic, shifting the agency’s perspective in a more punitive direction. But the bills’ authors want CISA to continue to be viewed as an ally.

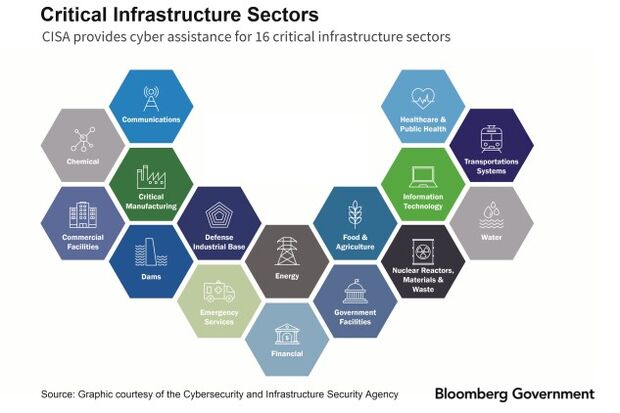

To date, there is no singular cybersecurity reporting requirement among the 16 critical infrastructure sectors designated by a 2013 presidential directive. Some of these sectors have regulatory agencies that have set cyber requirements already, like the financial sector, whereas others such as the water sector have no cyber mandates.

The bills would require certain critical infrastructure operators designated by CISA to report cyber incidents to the agency no later than 72-hours after the event—a timeline that’s been backed by numerous industry sectors that say a shorter reporting requirement could lead to rushed or false positive reports.

Both Sens. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) and Rob Portman (R-Ohio), the chairman and ranking member of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee and sponsors of the Senate bill, want CISA to be a helping hand.

“What we intend to do is to keep CISA in a situation where companies feel very comfortable seeking their advice, setting best practices and providing information that can help other companies,” Portman said in an interview. “But no, we don’t want to make them into a regulator.”

Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) thinks CISA can be both partner and enforcer. “I don’t think those two things are necessarily in conflict,” he said.

Easterly says she wants CISA to be viewed as a “trusted partner” for information sharing and has prioritized collaboration to defend against hackers. This summer, CISA launched the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative, a public-private partnership with Amazon.com Inc., Microsoft Corp., Alphabet Inc.‘s Google and government agencies like U.S. Cyber Command, the National Security Agency, and the FBI to develop a cyber defense plan initially focusing on ransomware and cyberattacks on cloud companies.

Enforcement Tools at Play

CISA is still pushing for stronger enforcement mechanisms in the legislation that is expected to move on a year-end defense authorization bill.

The legislation would give the agency administrative subpoena authority. But Easterly has said the authority to fine companies would help the agency act quickly. That tool could put CISA more squarely in a regulator role.

“An enforcement mechanism with greater teeth would be helpful, but we think administrative subpoenas are a very useful tool,” she said. Subpoenas are “slower than where we need to be because the adversaries operate in an unconstrained world; we need to be operating at the speed of cyber,” Easterly said.

Enforcement tools are necessary after years of lax voluntary reporting and few consequences for failing to report cyberattacks, said Bryan Ware, CISA’s former assistant director for the cybersecurity division during the Trump administration. “Without any penalty, we just haven’t seen enough partnership, enough transparency and really enough credibility placed upon CISA,” Ware said in an interview.

Representatives from some of the industry sectors affected say while they understand the carrot and stick approach, fines would be too punitive for companies recovering from a cyberattack.

Fines would “actually exacerbate an adversarial aspect to an area that we need to work on collaboratively and in cooperation, we believe that subpoena is the appropriate mechanism,” said Robert Mayer, senior vice president of cybersecurity at communications trade group USTelecom.

The lawmakers say the legislation will set a baseline for all critical infrastructure operators to follow, but specific sector regulators like the Transportation Security Administration could set more stringent cyber requirements. For instance, TSA has issued mandatory cyber directives for gas pipelines and is planning mandates for rail and airline operators as well.

“There’s a general recognition that a voluntary approach doesn’t work,” Jim Lewis, a senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said in an interview.

“People don’t want to admit that sectors that are more regulated do better at cybersecurity,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Rebecca Kern in Washington at rkern@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Zachary Sherwood at zsherwood@bgov.com; Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergindustry.com; Giuseppe Macri at gmacri@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.