Migrants in Limbo as Court Backlog Balloons and Costs Skyrocket

- Wanted: interpreters to help clear almost 1 million cases

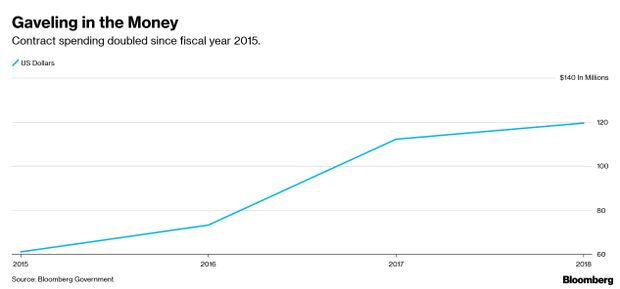

- Companies grab contracts as spending almost doubles

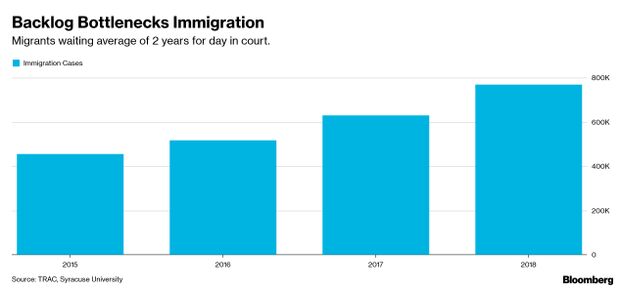

While the Trump administration continues to declare an immigration crisis at the U.S. border, legal and immigration groups say underfunded immigration courts are straining the system leaving migrants in limbo in the U.S. an average of two years before their day in court.

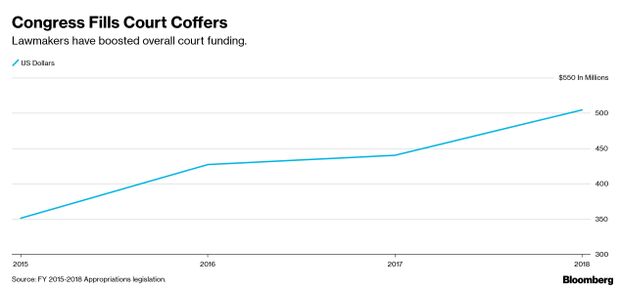

Spending at U.S. immigration courts has almost doubled to $119 million in fiscal 2018 from $61 million in fiscal 2015, an analysis of contracts shows. ManTech International Corp. and Booz Allen Hamilton Holding Corp. are among those getting contracts, according to the Bloomberg Government study. But despite the spending and lawmakers’ efforts to bolster the immigration courts, the backlog has also doubled.

As of January, the case backlog stood at 830,000, according to data from TRAC’s Immigration Project at Syracuse University. That doesn’t include potentially hundreds of thousands more cases caught up in procedural delays and the government shutdown earlier this year.

The court’s bottleneck has drawn ire and concern from both parties. President Donald Trump last year lamented that the pace spurs more undocumented migrants to cross the border and suggested, without evidence, that the long line leads to bribery and corruption. Meanwhile immigration and court advocacy groups and some Democratic lawmakers say the courts may be more fundamentally broken, and are being used as a political tool of the administration to rob asylum seekers of due process.

“It doesn’t matter how much money you throw at it, it’s broken,” Judge A. Ashley Tabaddor, speaking in her role as the president of the National Association of Immigration Judges, a union, said in an interview.

A new pot of funding provided by Congress in February laid out even more money for contracts as well as judge and clerk salaries. Still, current and former judges and legal groups say it remains insufficient to dent the backlog, and disagree over what mix of policies and funding would help. Some suggest a complete restructuring of the court outside the political confines of the Justice Department, while others urge more judges, policies to speed consideration of cases, tighter immigration laws, and more technology.

“We’ve got to reduce the time to initial termination of immigration cases,” Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), chairman of the Senate Homeland Security Committee, said in an interview, pointing to the new waves of families and children trying to cross the border.

Driving the Spending

The largest portion of the immigration court system’s contract costs stemmed from an increase in interpretation service, according to the Bloomberg Government analysis. A spokeswoman at the Justice Department confirmed that finding, saying such services cost $60 million last fiscal year and are expected to increase again this year.

Virginia-based interpreter service SOS International LLC was the courts’ top vendor, growing to $38.9 mllion in fiscal 2018 contract obligations, compared with $9.3 million in fiscal 2015. Representatives from the company, as well as other top vendors and interpreter services, such as Vera Institute of Justice Inc. and Lionbridge Technologies Inc., declined or didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Interpretation spending is being driven in part by an increase in hearings for non-English speakers, the rate structure of the contracts, and a doubling of the number of asylum applications between fiscal 2016 and 2018, the Justice spokeswoman said.

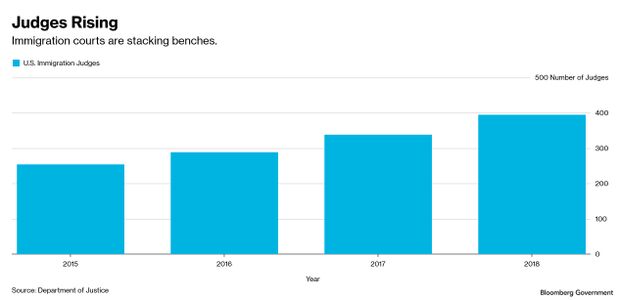

An increase in the number of judges hired, as well as a series of quota and deadline polices then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions put in place increased the pace of processing cases, she said.

Driving the Backlog

Spikes in immigration over the past decade have increased the docket, and multiple reports from government watchdog groups have made recommendations that have yet to reverse the trend.

The immigration court office in its budget justification last year said the backlog stemmed from a mix of factors, such as challenges in hiring judges quickly, and more immigrants seeking to stay in the U.S., as the Department of Homeland Security—which houses Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Customs and Border Protection and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services—steps up efforts to deport them.

“For years the immigration courts have been underfunded, and there has been more emphasis on funding the DHS enforcing agencies,” Laura Lynch, senior policy analyst at American Immigration Lawyers Association. She points to a court budget that is a fraction of that of ICE and the Border Patrol.

The growing number of families and children from Central America, who now account for more than half of all apprehensions at the Southwest border, requires more time to process and more frequently need indigenous interpreters, adding to costs, the department and legal groups said.

“You’re just going to see that balloon expand,” said Andrew “Art” Arthur, a former judge and fellow with the Center for Immigration Studies, who advocated for tighter immigration laws to deter families from making the journey in the first place.

Congress Response

Senator Johnson and lawmakers from both sides of the aisle have been quick to support increasing the number of judges to help ease the backlog, although Trump has disputed the need for more hiring and suggested doing away with the courts altogether. The Justice Department’s budget document said increasing the number of judges to 700 from about 400 currently would reduce the backlog by 15 percent. Arthur agreed with this target.

The American Bar Association, as well as Lynch’s lawyers’ association and Tabaddor’s judge’s association, have called on Congress to make the immigration courts independent from the Justice Department. The agency’s politics reduces judges’ abilities to manage their own caseloads, Tabaddor and Lynch said. Although the courts need more funding, the backlog won’t be fixed without a reorganization, they said.

Easing the courts’ caseloads is a priority, said Jose Serrano (D-N.Y.), chairman of the House Commerce, Justice, and Science Appropriations Subcommittee. His team is looking into contract spending, he said in an interview. He said he isn’t convinced the system was broken beyond what more funding could repair, but would look into the idea of a court restructuring.

“On one hand, you can’t backlog a system and say it doesn’t work, so you have to look at both,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Michaela Ross at mross@bgov.com and Paul Murphy at pmurphy@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com