Drugmakers Drag Feet as Congress Drills Into Prescription Prices

Lawmakers looking to curb rising costs consumers pay for prescription drugs want the industry to explain its pricing, but are finding pharmaceutical companies reluctant to reveal their secrets.

Several congressional committee leaders have opened investigations into how drugmakers price their products. Two House panels have sent letters to some of the country’s largest drugmakers asking for information about how they set prices and how they negotiate with industry middlemen on the sticker price for their medicines. The Senate Finance Committee is also signaling it wants drug industry executives to appear during a public hearing.

However, industry representatives said they’re reticent to hand over some of the information lawmakers are seeking and few want their executives to face questions in a Congress they see as hostile.

“Pharmaceutical companies look at what happened to Martin Shkreli and Heather Bresch at Mylan and they don’t want their company to be the face of this year’s drug pricing scandal,” Rachel Sachs, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis who studies drug policy, said. She was referring to the two drug-industry executives who were brought before Congress in 2016 to answer for their companies’ pricing decisions.

The industry’s foot-dragging probably won’t stop lawmakers from acting on the issue, Sachs said.

Committee leaders have hinted they’re willing to force companies to comply with their requests, if necessary.

Net Profits, Justifications?

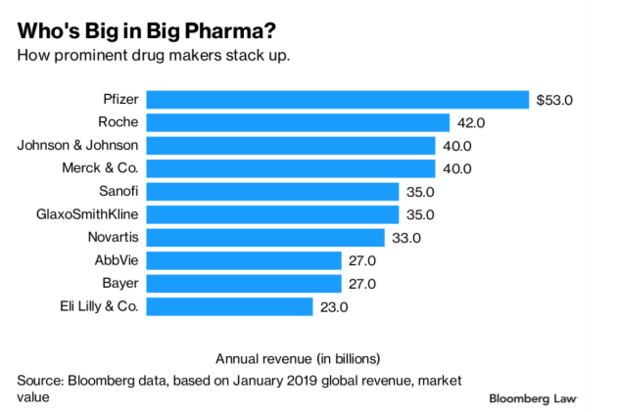

Two House committees–Oversight and Reform, and Energy and Commerce–have sent letters to a dozen major pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer Inc., Gilead Sciences Inc., and Sanofiasking for information about the price of their products, their net profits, and a justification for price increases.

The Oversight panel has asked for 10 years of pricing data and is seeking information about drug patents and how the companies protect those patents, according to an industry person. The letters haven’t been made public.

The same person said the company is working with the Oversight committee to answer the dozens of questions the panel sent but noted it isn’t likely to answer all queries out of fear of revealing a trade secret.

The Energy and Commerce letter, sent Jan. 30, focused on the makers of insulin and asked if they’ve engaged in any regulatory stalling tactics or pay-for-delay deals to keep generic versions of products off the market.

READ MORE: The Insulin Wars, New York Times

Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.), chairwoman of the Energy and Commerce Committee’s investigation panel, said the companies she contacted last year for an investigation into the price of insulin– Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly & Co., and Sanofi—were all cooperative and she expects they’ll be helpful again.

However, she warned that her panel has the power to require private companies to respond to requests.

“We do have the ability to compel document production and we’ve done it before,” DeGette said.

`Show Up,’ Wyden Says

Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the Republican and Democratic heads of the Senate Finance Committee, publicly warned drug companies to make their executives available after several declined invitations to appear before their panel. Wyden even noted tobacco executives were willing to appear before lawmakers.

“The drugmakers are going to have to show up as well,” he said.

Grassley said only two companies agreed to appear before his committee. The Senate Finance Committee didn’t identify which companies it asked to testify.

The companies Grassley contacted are undisclosed. Among a raft of drugmakers contacted by Bloomberg Law, Roche Holding AG, Novartis AG, and GlaxoSmithKline PLC didn’t receive a letter from Grassley, representatives from each said.

“We have engaged with every member of the committee to provide information about Sanofi and the broader issue of drug pricing,” Sanofi spokeswoman Ashleigh Koss replied. “But we do not comment on the specifics of private conversations.”

Genentech, a Roche subsidiary, said the company is in discussions with the Department of Health and Human Services and others on proposals to improve the health-care system.

“We take decisions related to the prices of our medicines very seriously and our commitment to patient access and investment in future breakthroughs are reflected in our actions,” Genentech said in a statement.

Gilead Sciences—which sparked public outcry in 2013 when its blockbuster hepatitis C drug Solvadi came onto the market with an $84,000 price tag for 12 weeks of treatment—declined to comment on whether it received a letter from Grassley’s office or the Senate Finance Committee. The Foster City, Calif., pharmaceutical company announced last fall it would sell cheaper generic versions of its other hepatitis C drugs Epclusa and Harvoni. The brand-name versions cost more than $1,000 a pill.

Grassley didn’t ask the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America to testify, a representative of the brand-name drug industry’s trade group said in response to a query.

“As a trade association representing the industry, we can’t speak to how specific products are priced due to antitrust reasons,” the PhRMA representative said.

With assistance from Warren Rojas

To contact the reporters on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com; Jeannie Baumann in Washington at jbaumann@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com; Randy Kubetin at rkubetin@bloomberglaw.com